František Behounek and the Burst Balloon

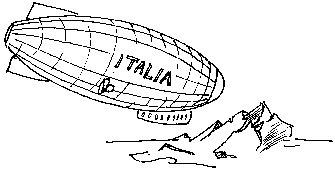

František Behounek, namesake for Jáchymov’s Behounek Sanatorium (see last month’s column), was Director of the Czechoslovak state Radium Institute in Prague. His measurements of radon concentrations in the Jáchymov mines played a key role in establishing the first concentration limit for airborne radioactive material: 10 pCi L-1 for 222Rn (Evans 1980). As a former pupil of Marie Curie, Behounek brought her mineral samples from an expedition he made to the North Pole with Roald Amundsen—Curie expected her students to bring back samples from trips they made to faraway places (Quinn 1995). This story is about another arctic voyage of his, the ill-fated trip in 1928 in the dirigible Italia.

Behounek almost didn’t get to go. The airship’s commander, Umberto Nobile, was concerned about the weight the ship could carry and Behounek was a big, big man. But at the last moment, Nobile relented and Behounek was allowed on board. Another of the ship’s scientists, the Swedish meteorologist Finn Malmgren, joked, "There’s an advantage for all the rest of us if you [Behounek] do come. If we find ourselves stranded on the ice, about to perish from hunger, we’ll always have something to live on…"(McKee 1979). But rather than serve as emergency rations, Behounek’s intent was to measure atmospheric conductivity and, most importantly, radioactivity. This is exactly what he was doing when the Italia suddenly began to lose altitude while flying over an ice pack north of Spitzbergen. Nobile’s valiant efforts to save his ship failed—the Italia was carrying too much weight and crashed into the ice. The survivors sustained themselves with food recovered from the airship and meat from a bear Malmgren shot with a revolver (remnants of the ship’s log were found in the bear’s stomach, he had been hungry too). But although they had food, they were in a weakened state. And some, such as Nobile, were seriously injured (McKee 1979).

At this point, I’ll turn the story over to Bertrand Goldschmidt who among other things was Chairman of the Board of Governors of the International Atomic Energy Agency. Quoting from Atomic Rivals (Goldschmidt 1990): "Behounek, the expedition scientist, did not wait for help (which arrived later by plane), and sought to regain solid ground on foot along with two other members of the expedition, one an Italian and the other a Swede [Malmgren]. The Italian and the Czech [Bhounek] arrived but without the Swede, whom the other two had eaten…after his death, of course. When I made Behounek’s acquaintance in the thirties at the Curie laboratory, he was very corpulent, proof that he had well recovered from his privations and his exceptional diet."

Gadzooks! Can this be? One day Behounek’s measuring atmospheric radioactivity and the next day he’s chowing down on a dead Swede! A nuclear scientist degenerating into cannibalism so quickly!

Alas, it is my distasteful duty to burst this balloon. Malmgren and two others did set off on their own. It is also true that Malmgren died and that reports of cannibalism appeared in the popular press. But Behounek was not involved. He had stayed behind with Nobile and the rest of the main party. Malmgren’s traveling (and dining?) companions were two Italian naval officers (McKee 1979; Holland 1994).

Goldschmidt’s story is a choice one. I just wish it were true—in fact, I’d give an arm and a leg.

References

- Evans, R.D. Origin of standards for internal emitters. In: Health Physics: A Backwards Glance, Kathren and Ziemer (ed.). Pergamon Press, New York; 1980.

- Goldschmidt, B. Atomic rivals. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick; 1990.

- Holland, C. Farthest north. Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., New York; 1994.

- McKee, A. Ice crash, disaster in the Arctic, 1928. St. Martin’s Press, New York; 1979.

- Quinn, S. Marie Curie, A life. Simon and Schuster, New York; 1995.