Radium Emanator Filter Jar (ca. 1930)

The Radium Emanator Filter was invented by John Wichmann of Los Angeles (ca. 1926). Quoting from one of his two patents related to the jar:

"My present invention is designed to highly charge the water such as may be required for professional purposes, in which the water having a certain number of Mache units, is to be taken according to a physician's prescription. The filter emanator may also be utilized as a general device for charging water with radium emanation for household use."

As a nice decorative touch, the jar was made from uranium (vaseline) glass and it is the uranium that is responsible for the beautiful greenish-yellow glow under UV illumination (photo above right). The uranium (natural rather than depleted uranium) wouldn't add significant radioactivity to the water, but it does produce a slight increase in the exposure rate immediately adjacent to the jar.

The device (not the glass jar itself) was manufactured by the Radium Emanator Filter Co. Inc. of North Haledon, New Jersey. Their address was 1263 Belmont Avenue.

On the upper half of the jar, you might be able to make out a large smooth area where the paper label would be affixed. Paper labels on water jars is not a good idea. Anyway, the text on the label read:

DRINK RADIOACTIVE FILTERED WATER

RADIUM EMANATOR

THE BETTER WAY TO HEALTH

RADIUM EMANATOR FILTER CO., INC.

1263 BELMONT AVE.

PATERSON, NORTH HALEDON N.J.

U.S.A.

More information about John Wichmann and the Radium Emanator Filter Company can be found farther down this page.

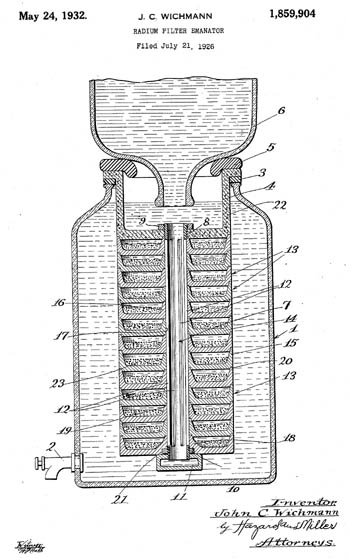

In the 1990s, a number of these jars were discovered in a New Jersey warehouse owned by the family of the manufacturer. This is undoubtedly one of those. None contained the radioactive source (emanator) described in the patent and shown in the diagram to the right.

Size: ca. 21" high, 9 1/2" diameter at widest point

Exposure rate: ca. 4 uR/hr above background on contact. Nothing detectable at one foot

John Carl Wichmann - Important Dates and Facts

1872. John Carl Wichmann was born August 1 in Hamburg, Germany.

1881. His future wife, Nell Orr, was born June 7 in South Carolina.

1894. Wichmann moves to the United States.

1907. Wichmann seems to be a representative for Ehrich and Graetz, a Germany lamp/lighting manufacturer.

1908 to 1922. The Bureau of Investigation, predecessor to the FBI investigates his activities involving Germany.

1916. Wichmann was in Los Angeles and identifying himself in the City Directory as vice president of the M and W Mining Company (Maier and Wichmann Mining Company).

1917. Wichmann went to trial in 1917 for defrauding Edward Maier.

1921. Wichmann becomes a naturalized U S citizen. His passport application describes him as a chemical engineer.

1926. Wichmann submits two patent applications for his Radium Emanator Filter jar.

1930. John and Nell were living in Greenville, South Carolina.

1932. The State of New Jersey de-listed Radium Emanator Filter Company, Inc.

1943 and 1947. John and Nell filed patents for a “Gasoline Conserving, Power Increasing Vaporizer.”

1947. John Wichmann died December 7, 1947.

1961. Nell Wichmann died on the 27th of February in Los Angeles.

Representative for Ehrich and Graetz

The first of Wichmann’s business activities I know of involved Ehrich and Graetz (E&G), a well-established German manufacturer of gas and liquid-fueled lamps. In 1907 he published an advertisement in Light, an industry publication that he was serving as a representative in the U.S. for E&G. The problem the publishers had with his ad was that it gave his address as John C. Wichmann, Diplon-Eng, care of Light Publishing. This forced the publishers to print a lengthy notice in a subsequent issue that read in part: “there is absolutely no connection whatsoever between the Light Publishing Co. nor anyone connected with it and the concern named [E&G] or its representative [Wichmann].”

Wichmann took notice of their complaint because his next advertisement in Light indicated that his address was “John C. Wichmann, Diplon.-Eng. Care of Fensterer & Ruhe.’’ The latter were Importers of Glass and Ceramics.

What this suggests is that Wichmann was using the addresses of other companies in order to acquire credibility. If he actually worked for Ehrich and Graetz, he wasn’t high enough on the food chain to be given an office.

Mining Tungsten

In March of 1913 (the year the Coolidge tube was invented with its tungsten filament and target), Wichmann is identified in press accounts as “a noted metallurgist of Berlin, Germany” who was head of the American Tungsten Mining and Refining company (San Francisco Call. Mar. 30, 1913). The article indicated that the company was constructing a facility in Los Angeles for converting the concentrates into tungsten metal. Furthermore,

“A tungsten strike of impressive proportions was made last week in the Sageland and Kelso mining districts [near Randsburg, CA a desert mining town]... many mining men are taking a keen interest in the new strike.”

I wish I knew more about his tungsten mining operation in the California desert. Perhaps its main purpose was to line up financial backing for his next scheme: tungsten mining in Arizona.

Two years later Wichmann was in Prescott, Arizona and he had money to spend. The local press reported as follows:

“Dr. J.C. Wichmann of Los Angeles, prominently known in mine investment circles... travels in a large auto, with his two engineers... It is quite probable he will be an investor.” (Weekly Journal Miner. Oct. 27, 1915).

The prediction was spot on. Within three months a Nogales newspaper would report

“John C. Wichmann, who recently took over the tungsten mines twelve miles east of Yucca... reports that a wonderful body of tungsten ore has been opened." (Border Vidette Jan. 29, 1916).

The money to purchase these properties came from Edward Maier, a wealthy Los Angeles brewer. Wichmann had convinced Maier to provide the financial backing for a company in which they would be equal partners, the Maier and Wichmann Mining company.

The M and W Mining company was short-lived. The problem was that Wichmann was taking more money from Maier than he was spending, e.g., Wichmann told Maier, that one group of claims was purchased for $2,400 when the actual cost was $1,500. All told, Maier estimated that he lost some $45,000 (Prescott Journal Miner, Sept. 5, 1916).

Things looked bleak for Wichmann in late 1916. Arrested on a federal charge of using the U.S. mail to defraud Maier, he went to trial in March of 1917. Fortunately for Wichmann, the case was complex and involved a lot of legal technicalities. Wichmann was acquitted (Mohave County Miner, Mar. 24, 1917).

The Synthetic Rubber Products Company

Wichmann’s next business was rubber. In 1920, he and two men from Elkhart, Indiana formed the Synthetic Rubber Products Company. The articles of incorporation indicated that they were capitalized to the tune of $3,000,000. It’s fair to say that Wichmann would supply the brains and the other two supplied money. (India Rubber Review. Vol. 20. May 15, 1920).

Wichmann claimed to have invented a new process for making synthetic rubber using the Yucca plant. The details of the process were described in two patent applications (1,435,359 and 1,435,360) that he filed in 1921. Both applications were titled: “Process of Making a Rubberlike Material.”

Sales of the company stock were heavily promoted in Princeton, Indiana, a good distance away from the company “headquarters” in Elkhart and the company’s “production facility” in southern California.. Wichmann even had the cojones to set up a demonstration of his rubber making process in the basement of the town’s courthouse. Sales went extremely well, annual returns of 25% were predicted, but this proved very unfortunate for Mr. Henring, a local landowner/businessman who acted as guarantor for many of the promissory notes used in the stock purchases. When the Synthetic Rubber products went into receivership, sometime in 1921 or 1922, Henring was stuck owing $66,000 according to the Poseyville News (July 21, 1922). The newspaper commiserated with Henring by noting that it wasn’t strange that

“some of our best citizens . . . should fall for it.”

The “it” being “making one of the most valuable of commodities out of cactus, one of the most abundant and cheapest.”

Wichmann escaped the legal fallout, but not those he had arranged with to sell the stock. The latter were charged with “conspiracy to swindle and defraud” and hauled into court (Brazil Daily Times, Jan. 11, 1923).

Pecos Oil

In late 1923, the same year that his associates were charged with the fraudulent sale of stock in his Synthetic Rubber Products Company, Wichmann had switched careers paths. Never missing a beat, he was now in the oil business.

The October 5, 1923 issue of the Pecos Enterprise told its readers what they needed to know. Those of them interested in making money that is.

“Dr. John C. Wichmann, Los Angeles capitalist, came... to look over the Pecos oil field... Dr. Wichmann expresses himself as well pleased with the prospects... beyond question we have a grand oil field here which only needs development.” “[Wichmann] has plenty of friends who are also capitalists, who will go full length with him in the development of the Pecos oil field.” “the royalties alone would make those interested rich.”

Wichmann indicated that his company intended to construct a refinery near the oil field. It would use

“a process of refining oil, discovered by Germans during the war, which materially reduces the cost”

The article concluded:

“big things are about to reveal themselves in the Pecos oil field in the near future.”

I wish I had additional information about his Pecos oil operation, but it couldn’t have ended well for anyone but Wichmann. And maybe, not even him. His Buick touring car was put up for sale in October of 1925 by Pete’s Service Station because of an unpaid repair bill for $21.50 (Pecos Enterprise, Oct. 1925). Of course, Wichmann had probably “purchased” it using promises and/or other people’s money.

Rubber Redux

Several years later, in 1927, multiple newspaper accounts appeared that promoted Wichmann and his method for producing synthetic rubber from cacti. One identified an invention that modesty might have prevented him from mentioning himself,

“friends claim for Wichmann the invention of the first tungsten filament electric light” (Bakersfield Californian. Aug. 24, 1927).

As likely as not, he was trying to duplicate his earlier success with the Synthetic Rubber Products Company and was fishing for investors. To be clear, that company wasn’t a success. It imploded in 1922. But Wichmann probably turned a nice profit in the process. That’s success.

Wichmann's Patents for the Jar

In 1926, Wichmann submitted two similar patent applications. The first, for the Radium Emanation Jar (1,817,329), would be issued in 1931. It described the overall construction of the jar. The other patent, for the Radium Filter Emanator (1,859,984), was issued in 1932. It described the construction of the emanator (i.e., the source).

The Radium Emanator Filter Jar

In 1928, the Radium Emanator Filter Company of North Haledon, New Jersey was incorporated with the purpose of “manufacturing filter devices.” It was capitalized at $100,000 (New York Times, June 15, 1928).

Arthur A. V. Ginoti of Haledon New Jersey was the only name associated with the incorporation papers. Ginoti is a mystery man—I have managed to learn nothing about him—help in that regard would be appreciated.

North Haledon, New Jersey was an ideal location—it was just down the road (more or less) from Orange, N.J., where radium was readily available.

The uranium glass jars that Ginoti used were produced by the McKee glass company of Jeanette, Pennsylvania (the McKee company was identified on a cardboard box that one of the jars came in).

Unfortunately, Ginoti's timing was bad. By 1932, when the patents were finally granted, the country was in a depression and the state of New Jersey was rescinding the Radium Emanator Filter Company’s incorporation. Presumably, Ginoti had not been paying his taxes.

John and Nell's Increasing Vaporizer

In 1943, the 71 year old Wichmann and his wife Nell submitted a patent application for a “Gasoline Conserving Power Increasing Attachment.” The patent (2,415,691) which was issued February, 1947 described a

“simple, compact, inexpensive device... [that would] materially increase [a vehicle’s] power development... provide for smoother, more flexible engine operation, quicker acceleration, increased mileage of travel and absence of knock or ping.”

You can imagine John on a late-night television infomercial (had they been running back then) selling this miracle device for $29.95, and including, for a limited time only, a second one at no additional cost (except for the S&H).

Wichmann had a habit of taking out pairs of similar patents and this was no exception. In June of 1947, John and Nell submitted a patent application for a Gasoline Conserving Power Increasing Vaporizer. The patent (2,477,708) was awarded in 1949, but it came a little late—John died in December of 1947 at 75 years of age.

Reference

Kolb, W. and Frame, P. Living with Radiation, The First Hundred Years. Syntec Inc. 2nd Ed. 2002.