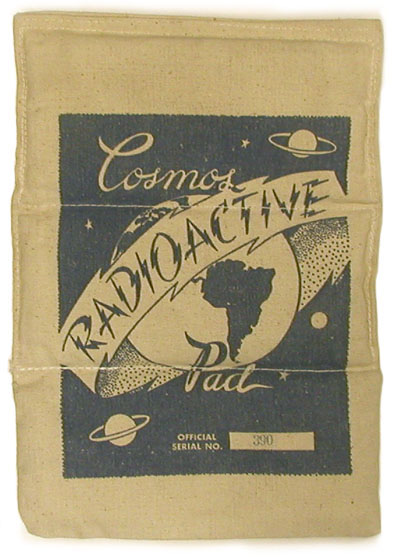

Cosmos Radioactive Pad (ca. 1950-1956)

Front of the pad.

The Cosmos Radioactive Pad was produced by Raco, Inc. in Seattle, Washington in the 1950s. George Kosmos was the company president. Information about him can be found toward the bottom of the page.

Like most such pads, it contains low-grade uranium (monazite) ore.

In 1955, the FDA issued a Notice of Judgment against the company based on their misleading claims that it "provided an adequate and effective treatment for arthritis, bursitis, rheumatism, neuritis, and sinus trouble, and soreness of hands, wrists, forearms and back."

Size: 8" x 12"

Exposure rate: ca. 50 uR/hr above background at one foot

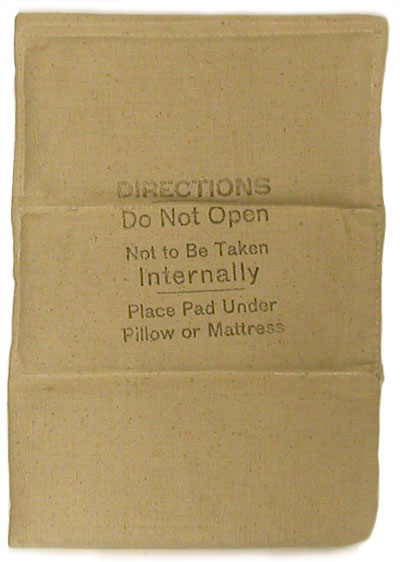

Back of the pad.

1891. Born in Arcadia, Greece July 26, 1891

1903. Immigrates to the United States (Redding, California)

1916. Living in Alaska.

1918. Has moved back to California

1928. Living in Shelton, Washington. Injured in car accident

1929. Moved to Seattle

1930. Incorporates the Stanwood Oyster Company, and served as its president

1940. Operated a bowling alley concessions stand. Manager of the Ideal Lunch, a restaurant/diner. President of the Pearl Oyster Company

1945. Greater Seattle Bowler of the Year

1945-1946. Operated a boxing promotion business (Western Athletic Club).

1949. Manager and vice-president of the Seattle Sourdough Club

1953-1957. Manufactured and sold the Cosmos Radioactive pad

1956. Alaska Sourdough Stories is published

1957. Sued the International Oil and Metals Corporation

1958. President of the American Metals Company

1973. Died at age 82

In late 1928, the Centralia Daily Chronicle (Nov. 20) reported that “George Kosmos, restaurant man and one of the most noted bowlers in the state [Washington], was scalped and burned” in a car accident. The most severely injured of those in the car, Theodore Deer, was associated with the Deer Oyster Company. What this unfortunate incident might suggest is that Kosmos developed his interest in the oyster business because of his involvement in the restaurant industry.

A year and a half later, and living in Seattle, George Kosmos incorporated the Stanwood Oyster Company. It was capitalized at $44,000 (Centralia Daily Chronicle, Apr. 24, 1930). The Arlington Times (July 23, 1931) noted that Kosmos was the president, J. L. Moore was the vice president, and P. J. Mahone was treasurer. A year later, the company seemed to be doing well, it had $287,970 in assets, 13,000 shares of common stock and was purchasing machinery and buildings with the intent to operate a canning factory. A deal had been struck with the Japanese fishing industry for 120,000 cases of tuna and the company intended to plant 60,000,000 oysters (Stone & Webster Journal, Vol. 47, 1930).

Kosmos was also credited with starting the Camano Blue Point Oyster Company (Exploring Camano Island: A History Guide, Val Schroeder, 2014), but he does not seem to have been involved with the company incorporation (Arlington Times, Jan. 1932). The incorporators were his old associates in the Stanwood Oyster Company: P. J. Mahone, A. J. Canon and O. E. Holmberg. The company’s prospects seemed good—it was capitalized at $1,000,000. Unfortunately, the oyster industry almost collapsed during the 1930s due to overproduction. In 1938, Kosmos was quoted as saying that it was unprofitable to harvest oysters at 24 cents per gallon when they could be purchased for 30 cents.

Despite the market downturn, Kosmos liked oysters—the 1940 Seattle City Directory indicated that he was president of the Pearl Oyster Company.

For some reason, Kosmos decided to get into the boxing business as a promotor. In September of 1945, the State Athletic Commission granted a license to Kosmos’s Western Athletic Club (Walla Walla Union Bulletin Sept. 12, 1945). Like most of his ventures, it was short-lived—he only promoted nine events, the last in September of 1946.

His management skills couldn’t have been the best because he booked the matches on Tuesday nights—the same time that he was supposed to be competing in the Seattle Classic bowling league (Daily Globe Oct. 25, 1945).

The press sometimes described him as a “sportsman.” What I can say in that regard is that aside from his brief career in boxing, he served as a guide on bear hunts, and he was a climber of sorts. He “almost—but not quite—made it to the top of Mount McKinley” (Daily Sitka Sentinel, July 3, 1973). He was also a fan of professional wrestling, but that might not count.

One more thing, he was a bowler.

Bowling King of Alaska

George Kosmos was not just any bowler, he was one of the best.

He rolled his first bowling ball in 1906 when he lived in Redding, California, and he remained involved in the “sport” throughout the rest of his life. By 1921 he was managing two bowling alleys in Sacramento. In 1928, after he had moved to Shelton, Washington, he would be described as one of the best bowlers in the State (Centralia Daily Chronicle, Nov. 20, 1928).

In 1940, Kosmos was living in Seattle and holding down several jobs. Among other things, he was running a bowling alley concession stand.

A few years later, he was the secretary of the Northwestern International Bowling Congress (NIBC). In that role, he oversaw the NIBC’s largest competition with 1300 singles competitors as well as 750 doubles teams (Walla Walla Bulletin, Apr. 17, 1946).

Even at 64 years of age, he was good enough to win the 1956 annual Fourth of July Championship in San Francisco.

In recognition of his achievements and contributions, he was elected into the NIBC Hall of Fame in 1963.

His coolest title was probably “Bowling King of Alaska. During his “sourdough” years in Alaska (1916), Kosmos (aka “Klondike”) and Chet Sheets tied for the Anchorage bowling league’s high average score. To settle the matter they each came up with $750 for a ten game roll off. The story goes that the spectators wagered close to $50,000 on the match. As luck would have it, the result was another draw. A re-match was scheduled, but it had to be cancelled because one of them had a sore thumb.

As we know, it’s a small world. Twenty-seven years later, in 1943, Kosmos and Sheets were living and bowling in the state of Washington. Their re-match, originally scheduled for 1916, was back on and it became the climax of a Red Cross benefit tournament. The winner, George “Klondike” Kosmos, became the “1916 Bowling King of Alaska.” In 1943. (Daily Sitka Sentinel July 3, 1973).

In 1949, the Walla Walla Union Bulletin (July 26, 1949) indicated that the Seattle Sourdough Club was seeking a license to sell liquor by the drink. It was a short report, and for some reason it focused on the club’s vice-president and manager, George Kosmos. His annual salary of $7,000 was brought up. Now seven grand was pretty good money, roughly $70,000 in today’s dollars, and that’s probably why it was mentioned. The article also indicated that Kosmos owned stock in the company that owned the property rented by the Sourdough club (at $900 to $1,250 per month—$10,000 to $15,000 in today’s dollars). I can understand George wanting the club membership to have a drink or two.

In the early 1950s Kosmos, president of Raco Corp., began selling the Cosmos Radioactive Pad. Making money was surely his primary motive, but it would be nice to think that he believed in the pad’s ability to relieve arthritis and other ailments—which is what he claimed it could do.

Unfortunately, these claims violated the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, with the result that the feds came after him. The details of the case can be found in the FDA’s Decisions and Notices of Judgment (titles 5147 and 5078). Six 100 lb bags of radioactive ore had been shipped in 1953 from McCall, Idaho to Seattle, Washington where Kosmos packed the ore into 9” by 12” canvas bags. In 1955, the ore, 105 filled bags and 200 empty bags were seized. The confiscated material was destroyed, apparently with Kosmos’s consent, the following year.

It might have been possible to continue selling the pads, at least in-state, as long as he avoided making medical claims, but he doesn’t seem to have done so. There were better ways to turn a profit.

That brings us to the Idaho-based supplier of the monazite sand used in the pads. This, I believe, was the International Oil and Metals Corporation. Oddly enough, they were incorporated in 1956, the same year that Raco, Inc (Kosmos’s radioactive pad business) was going under. International Oil and Metals Corporation probably regretted the whole thing—the following year (i.e., 1957), Kosmos took them to court in order to recover $4,632.35 in interest and costs (Salt Lake Tribune, Nov. 1, 1957).

A large percentage of the people who produced “radioactive quack cures” were scam artists, and they had a lot in common. Their scams usually involved mining and the recovery of valuable metals (e.g., radium). Inevitably, some new process would be used that would make the operation more efficient. All these “businessmen” needed was financial backing.

Well by golly, in 1958 “George Kosmos, president of the large Seattle firm” American Minerals Company was telling the press that it was “very likely” that they would soon begin recovering mercury from deposits just outside of Morton, Washington (Centralia Daily Chronicle Aug.20, 1958). Although the deposits had been previously worked and abandoned, Kosmos indicated that he was experimenting with a new electrochemical process for the recovery operations. There was no reason for the reader to assume that this was a “fly-by-night” company, they already owned one mercury mine in California and two in Nevada. Then again, the mines might have been in Texas and Nevada (Centralia Daily Chronicle June 28, 1958). A minor discrepancy, the press sometimes gets things wrong.

The timing was good. Mercury was in demand and its price was high. One reason, as noted in the Centralia Daily Chronicle, was that the government was purchasing large amounts for the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), although the amount and purpose were being kept secret. Today we know that the AEC was employing millions of pounds of mercury to alter the isotopic composition the lithium used in thermonuclear warheads.

By no means should the above be taken to suggest that Kosmos was a scam artist. He was probably trying to make American Metals Corporation a success. What I suspect is that someone convinced Kosmos to purchase the controlling interest in a company without real assets or the prospect of ever having any.

Unfortunately, I have no idea how the American Minerals Company story concluded, or what any of his subsequent business activities might have involved.

Donated by Boeing Co. courtesy of Howard Wallace.

Reference

FDA. Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Notices of Judgment. 5078, 5147. Disposition 9-24-56

Nuclear craze: 4 ways atomic policies and products of the 1950-60s influenced Hollywood and American consumerism

The fascination with all things nuclear started during World War II and continued for a couple decades. What fed into (and perpetuated) the craze? This blog offers four reasons nuclear science was at the forefront of pop culture throughout the 1950s and 60s.