R. W. Thomas, the Revigator and the Thomas Cone

R. W. Thomas and the Revigator

Paul W. Frame

Ralph and Charlotte Thomas

Ralph W. Thomas was born December 10, 1873 in Kansas. By 1917, he was working in Arizona as a stock salesman. The 1930 U.S. Census estimated that his wife Charlotte was born 1877 in Illinois. Although I have no specific information concerning their marriage date, it was no later than 1928. For some unknown reason, Ralph and Charlotte ended up on the west coast. Southern California to be precise.

The Thomas Radium C. R. Jar (1921-1924)

The earliest reference that I have found to the Thomas Radium C. R. (aka Thomas Radium Ore) jar is a short note in the February 1921 issue of Popular Science Monthly (Vol. 98):

"Pottery is now manufactured which has in it a small percentage of radioactive material. This is mixed with the clay and baked in the kiln. Water left in the pottery of this nature for a short time will become radioactive by induction, and a health-giving drink is made. Such water may also be employed in the watering of plants with good results, since the presence of a radioactive compound near the roots of a plant is very helpful to its growth."

It is true that Thomas's name wasn't mentioned, but without a doubt, it was his jar that was being described.

Later that year, Thomas placed the following advertisement in the November 5, 1921 issue of the El Paso Herald:

RADIUM ORE

that will keep you supplied with soft Radio Active Water for generations is the greatest remedy and cure ever discovered for each and every disease. I furnish the ore,

R.W. Thomas

Hotel St. Regis

In 1923, Thomas placed an advertisement in the LA Times (December 9, 1923) offering a $500 reward to anyone with a "Thomas Radium Charging Jar" that failed to produce radioactive water. The ad identified the company address as 343 South Hill Street—not far from a location that would later be used by the Revigator Radium Water Jar Company, 319 South Hill.

The first explicit reference that I have seen to the "Thomas Radium Ore" jar is in a brief ad in the January 21, 1924 issue of the Bakersfield Californian. Similar ads for the jars continued to appeared until November of that year. Typical of these ads was one that referred to the “JARS OF LIFE” and the “radiumized” water that the jar produced. Three sizes were available: 2, 4 and 10 gallons.

All of the Thomas jars that I have seen are stenciled with the text "Thomas Radium C.R.," so the question naturally arises, "What does the C.R. refer to?" The answer can be found in an illustrated McKinstry & Hodgban advertisement that appeared in several April 1924 issues of the Santa Ana Register. The ad's illustration shows the following text on the jar: "Radium Charging Receptacles." There you have it, C.R. refers to Charging Receptacle(s).

Some background regarding the development of the jar was provided in an advertisement from the December 12, 1924 issues of the Bakersfield Californian and the Berkeley Daily Gazette. The advertisement (Radium Jars (Thomas) stated:

“Ten years ago [i.e., 1914] Mr. Thomas, an inventive genius, began his experiments” and “set about to relieve the sick and afflicted by daily restoring this element [i.e., radioactivity] to water by means of his “Radium Jar.”

Additional background information can be found in what I believe was the first brochure for the Revigator (in late 1924 the Thomas Radium C.R. jar became known as the Revigator). The brochure, with a copyright date of 1925, was titled “The Perpetual Health Spring in Your Home.”

It explained that R.W. Thomas, an invalid, was aware that Curt Schmidt in Germany had developed a method to incorporate purified radium into clay blocks that would then be placed in water. When enough time had passed for the water to become charged with radioactivity, the water would be consumed. Thomas believed that such water would be greatly beneficial his health. Unfortunately, the radium that Schmidt used was extremely expensive. The brochure continued:

“But Thomas was a poor man and could not afford to buy one of these expensive apparatus. He despaired that he could not raise the money to secure the relief of his affliction. Then he had an idea: “Since these great Radium Springs derive their power from washing against RADIUM ORE under the ground,” thought Thomas, “why can I not be cured by securing some of the same ore and placing it in contact with water.”

After several months of experimenting with some ore that he obtained from a miner in the Colorado Mountains, Thomas:

“succeeded in lining his first jar with the selected radium ores, then he secured a kiln and burned it for many days. When it had cooled, he filled it with ordinary city water and after drinking it for a few days, began to see definite signs of relief. He was so elated that he made other jars and loaned them to various afflicted people... from one person to another its reputation spread until soon Mr. Thomas found himself in the sole business of trying to supply the demand.”

How large had the demand become? Quoting the previously mentioned advertisement from December 12, 1924:

“Several thousands of these Thomas Radium Jars are doing daily service in Pacific Coast homes... Mr. Thomas’ business grew from two jars a month in 1922 to a point that our Pacific Coast production is over 5000 monthly.”

This suggests the possibility Thomas could not keep up with the demand for his jars and that he decided to sell his company, something that he did in late 1924.

In 1928, the El Paso Evening Post (April 23, 1928) claimed some of the credit for helping Thomas (described as being an El Paso local) find a buyer for his company. The article titled "Post Bureau Aids Inventor—Information Helps Finance Radio Water Device" indicated that someone at the Post's Washington bureau arranged for the radioactive content of jar's water to be analyzed by the National Bureau of Standards. The positive results presumably helped Thomas "in convincing capitalists that his invention was valuable." This might or might not be true, but I don't believe Thomas lived in Texas.

Although the Thomas Radium jars were in production for a relatively short period of time (ca. 2-3 years), there was significant variability in their design. The most commonly encountered version was a cylindrical jar with the straight sides, but there were also jugs and barrel-shaped jars. These different designs must have made mass production more of a problem (assuming they were in production at the same time).

The above photos show the two types of Thomas Radium Ore jars in the ORAU Collection. Oddly enough, the most common version of the Thomas jar is not in the collection, the cylindrical jar with the straight sides.

The above photos show the two types of Thomas Radium Ore jars in the ORAU Collection. Click on an image for more information. Oddly enough, the most common version of the Thomas jar is not in the collection, the cylindrical jar with the straight sides.

The Radium Ore Revigator

In late 1924 (October/November?) Thomas' company was purchased by the Dow-Herriman Pump & Machinery Company of San Francisco. The new operation, known as the Radium Ore Revigator Company, was based in San Francisco at 260 California Street. It is not particularly important, but the San Francisco City Directory from 1920 locates the Dow-Herriman Co. at 140 Howard Street and the Dow Pump & Diesel Engine Co. at 311 California Street.

The “Revigator” and the “Radium Ore Revigator Company” made their first public appearance (so to speak) in a notice that appeared in the November 25, 1924 issues of the Bakersfield Californian and the Berkeley Daily Gazette, and in a larger advertisement in the Los Angeles Times. The later referred to the jar as a German invention that was being made available in North America for the first time - with the end of WWI, hostilities had ceased between the U.S. and Germany. A graphic in the ad illustrated a Maltese Cross becoming a cross of the type associated with medicine. As the ad explained it:

"The black cross of war has been displaced by the white cross of health."

A brochure for the jar titled “Radium Ore Revigator for Every Home” (see the middle image below) stated

“Where a year ago the Radium Ore Revigator Company operated as a division of the Dow-Herriman Pump and Machinery Company, now the Revigator has grown to such an astounding pace that the Dow-Herriman has retired from the pump and machinery business and is almost absorbed completely in this newly born health giant, the REVIGATOR.”

The brochure’s copyright date was listed as 1924, but this is clearly a mistake because the Revigator company didn’t exist prior to late 1924. The brochure also claimed that prior to purchasing Thomas’ operation, Dow-Herriman spared:

“neither time nor money” in their “efforts to substantiate . . . the almost unbelievable health results that early users of this invention [the Thomas Radium C. R. Jar] had obtained.”

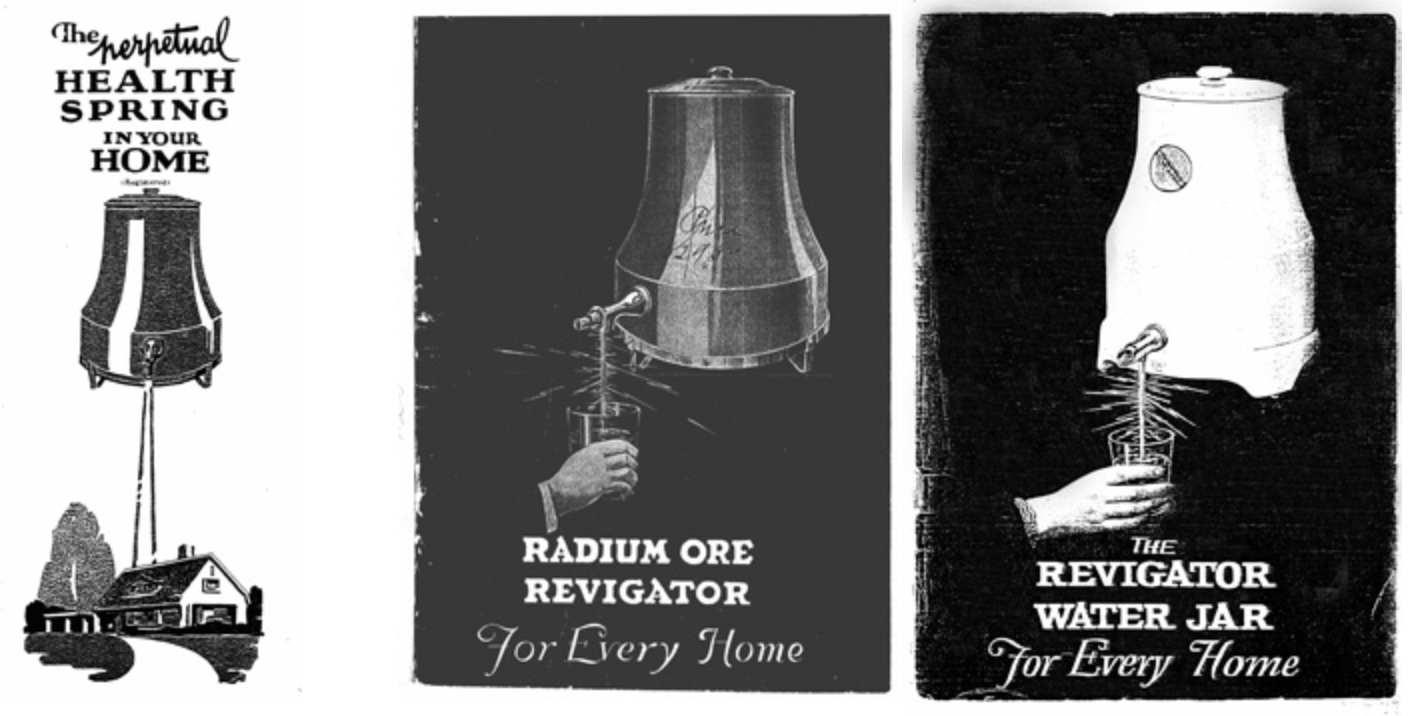

The Three Brochures

The above figures show the covers of what I believe were the only three brochures for the Revigator jar. That on the left has a 1925 copyright date. My guess is that the brochure in the middle was produced in late 1925 or sometime in 1926. It has a copyright date of 1924 but that is clearly incorrect based on its contents. The figure on the right shows the last brochure for the Revigator—it has a copyright date of 1928.

The Revigator Building

Sometime in 1925, the Radium Ore Revigator Company moved from 260 California Street to the “Revigator Building” at the corner of Sutter and Taylor Streets. The latter's street address was 693 Sutter. The sales department was at 697 Sutter.

The last reference I have found indicating that the company occupied 260 California Street dates from February of 1925, while the earliest reference to the “Revigator Building” is from September of that year (an advertisement in the September 2, 1925 issue of the Oakland Tribune).

The reason for the move, and this is pure speculation, might have been to consolidate the administrative offices and the manufacturing operation into one building. Until that point, management might have operated out of the 260 California Street location in San Francisco while the jars might have been produced in Los Angeles, possibly at 319 South Hill Street. Some of the company's advertisements described the latter address as a manufacturing and distribution operation. There is another possibility though. The move to the Revigator Building seems to have occurred when there was a shakeup of the company's upper management. It might have been that the outgoing president of the company (R. P. Sherman) controlled the lease for 260 California Street.

Without doubt, 1925 was a very good year for the Radium Ore Revigator Company. They were producing thousands of jars per month, and they had a new headquarters in their very own building.

The three jars shown above are the most commonly encountered versions of the Revigator. The tan jar on the left as probably dates from late 1924 to 1926. The blue jar is more likely to date from 1925 or possibly 1926. Both these jars refer to 260 California Street, an address that the company stopped using in late 1925 when they moved to the Revigator Building. The white jar on the right was likely manufactured between 1927 and 1930.

The figure to the right shows a scarce and unusual version of the Revigator. The body is a tan colored ceramic cylinder printed with the same design and address as that on the larger tan jar. This is also the same as what is engraved on the metal case. But the printing on the jar is smudged, possibly intentionally. On top of the smudged design is pasted a circular paper label identical to that used on the large white Revigator jar. The label identifies the company address as the Revigator Building. This suggests that the jar was manufactured in early 1925 before the company moved from 260 California Street to the Revigator Building. The label might have been added to correct the address. That's one possibility.

Robert P. Sherman: First President of the Radium Ore Revigator Company

Robert P. Sherman typically described himself as a Capitalist, but his major source of income was real estate. In the 1925 Los Angeles City Directory, the listing for the Radium Ore Revigator Company identifies R.P. Sherman as the company president and Elmer Haslett (SF) as its vice president. The Los Angeles address is given as 319 S. Hill.

The 1925 San Francisco City Directory listing for the company only mentions Elmer Haslett (as the General Manager). Sherman's personal listing describes him as "capitalist" and gives 260 California Street as his address.

The following year, the 1926 San Francisco City Directory identifies Haslett as the company president. Sherman no longer seems to be associated with the company—real estate might have been more to his liking that ceramic jars. Haslett and his company are no longer at 260 California Street having moved to the Revigator Building.

Elmer Haslett: President of the Radium Ore Revigator Company

Elmer Haslett was an interesting fellow. He was born in Missouri and lived in Mexico for a short period of time, but he spent most of his life in California. During World War I, he served as an observer with the 12 Aero Squadron of the U.S. Army eventually reaching the rank of major. He distinguished himself in the Army and in recognition received the Distinguished Service Cross for heroism in action over France. His memoir “Luck on the Wing” (1920) described his wartime experiences. The latter included the time he spent as a prisoner of war. He also wrote “Thirteen Stories of a Sky Spy.” By 1922, Haslett had left the Army behind and found himself in Mexico City as the Vice President and General Manager of the Mexican Finance and Investment Company. Not coincidentally, his uncle, the Executive President of Wells Fargo’s South American operations, was based in Mexico City. Perhaps unfairly, I suspect that the Mexican Finance and Investment Company had been created by his uncle as a vehicle to introduce Elmer to the business world.

Haslett’s time in Mexico was brief. The 1924 and 1925 San Francisco City directories record that he was working there as the Vice President and General Manager of the Mexican Finance & Investment Company. For what it is worth, these were the only years the company seems to have had a presence in San Francisco. Nevertheless, the thing worth noting is that his office was at 260 California Street, in the same building where the Radium Ore Revigator Company would open its first office in November of 1924. A reasonable guess might be that sometime in 1924 he came into contact with the Dow-Herriman Pump & Machinery Corporation. Perhaps he recommended that Dow-Herriman consider purchasing the Thomas Radium Ore Water jar company. Haslett might even have recommended himself as the manager for the new purchase. The other principle player in the Radium Ore Revigator company was its Treasurer and Secretary: D.W. Wurtsbaugh.

The “Revigator Water Jar Company”

In 1928 the company produced what I believe was the third and final version of their brochure for the Revigator. It was an update of the earlier brochure “The Revigator Water Jar for Every Home.” This time the brochure cover featured the white ceramic Revigator, the one in which the legs were an integral component of body of the jar. Sad to say, not a single mention of R. W. Thomas can be found in the brochure.

This new brochure referred to the corporation as the “Revigator Water Jar Co.” Perhaps the word “radium” was becoming something of a hot potato and they decided to drop it from the company name. Although the 1929 San Francisco City Directory still identified them as the Radium Ore Revigator Company, the 1930 and 1931 directories listed them as the Revigator Water Jar Company.

Its not clear how to interpret this, but a small classified ad in the December 11, 1931 issue of the LA Times indicated that the Revigator Water Jar Company "is entering the field with a new product" and that salesmen were needed. The latter were directed to a company address at 325 Fifth Street in San Francisco. If the Revigator Water Jar Company was no longer in the Revigator Building, things could not have been going well.

The Water Appliances Corporation of America

Sometime, and I am guessing in 1929, the Revigator company became a Division of the Water Appliances Corporation of America. The latter company was created by Elmer Haslett who also served as its president. No surprise there. The secretary-treasurer was D. W. Wurtsbaugh. In 1929, the first year that the company appeared in the city directory, their address was listed as being the 5th floor at 693 Sutter Street. The following year they relocated to 325 Fifth Street (1932 San Francisco City Directory).

This corporation seems to have been involved in buying up numerous, possibly failing, smaller companies. An advertisement in the May 7, 1930 issue of the Fairbanks Alaska Daily News Miner reads:

“Water Appliances Corporation of America includes the Standard Health Cup Co., Drink-O-Meter Co., Soft Water Stone Co., Wolf Patent Drip Co., Dow-Herriman Pump and Machinery Co., Black Charcoal Filter Co., the Fastidious Company, the Mineralator Co., Revig-a-Chick Co., The Revigorette Co., The Radium Therapy Corporation.”

Permit me to make a couple of comments about these subsidiary companies. The Dow-Herriman Pump and Machinery Co. was the operation that had purchased the Thomas Radium Ore Jar company in 1924. The Revigorette Company, located in the Revigator Building, produced the Revigorette, a very small version of the Revigator that was used to add radioactivity to face cream. The 1927 patent application for the Revigorette lists Elmer Haslett as the inventor. Not that it matters, but Haslett also patented a non-radioactive bidet.

The last appearance of the Water Appliances Corporation of America in the San Francisco City Directory was in 1932.

C. T. Spencer, the Last Revigator Salesman (maybe)

The only indication I have found that the Revigator was still being sold in 1930 was a series of advertisements for the “Revigator Water Jar Company” in various issues of the Fairbanks, Alaska Daily News Miner. The ads were placed by the brand new “branch office” of the Water Appliances Corp. of America. The office manager, C. T. Spencer, had previously worked in San Diego as a salesman of the Revigator Company.

Unfortunately for Spencer, 1930 was a bad year to be selling Revigators. The great depression had arrived. The deaths of the radium dial painters had been receiving extensive media coverage for more than a year. The Federal Trade Commission had just begun an extensive crackdown on companies selling products that contained, or claimed to contain radium for their misleading health claims. Yep, 1930 was a very bad year.

To make things worse, Haslett might have been getting ready to close down the business. It’s a terrible thing to suggest, but might Haslett have encouraged Spencer to open an office in Alaska (not yet a state) as a way to get rid of the last of his unsold inventory? Such a thought is both unwarranted and unworthy.

The last advertisement Spencer posted for the Revigator was in the July 18, 1930 issue of the Fairbanks Daily News Miner. The very next day the paper noted that he had departed town on a “business trip.” Soon thereafter, Spencer left for several months on a river excursion, primarily along the Yukon River.

Was there a specific event that led Spencer to disappear into the wilds of Alaska? Perhaps the news had reached Fairbanks that the Federal Trade Commission had issued a complaint against the Revigator Company in February of that year (1930). The charge: “Advertising falsely or misbranding as to government endorsement of product, and qualities and characteristics thereof; in connection with the manufacture and sale of earthenware water jars.” Even in the Fairbanks Alaska of the 1930s, there could be a good reason to get “away from it all.”

At various times during his “disappearance” Spencer (still identified as an agent for the Revigator Water Jar Company) would pen an article for the News Miner. In the one that appeared in the September 29 issue, he complained about how long he had been forced to wait in Nulato for a rail shipment of three Revigators from Fairbanks. He suggested that the railroad “purchase a few Revigator Water Jars and give the employees of the Alaska Railroad a few squirts of radium water to make them radio-active. It undoubtedly would improve the train service.”

C.T. Spencer, the last Revigator salesman, moved on to other things. In a couple of years he was working as a Deputy United States Marshall tracking down wrongdoers in the Alaska wilderness. The Daily News Miner was still reporting his exploits, e.g., a November 27, 1933 account of his investigation into the mysterious death of a trapper who appeared to have been eaten by animals.

The End

At the time of its death, a slow decay rather than a more merciful sudden demise, the Radium Ore Revigator Company had a dual identity as both a Nevada corporation and a Delaware corporation. The FTC’s final order regarding its 1930 complaint against the Radium Ore Revigator Company was issued September 20, 1934 (Volume 19 of the Federal Trade Commission Decisions Report). The order noted that one of the two Radium Ore Revigator corporations “went out of existence several years ago” while the other “passed into ownership of a third corporation and has gone out of business.” My guess is that the referred- to “third” corporation was the Water Appliances Corporation of America.

To his credit, Elmer Haslett, President of the Radium Ore Revigator Company, was present when the order was issued.

Ralph W. Thomas' Relationship with the Radium Ore Revigator Company

In late 1924, most likely October or November, the Thomas’s Radium Ore Jar company was purchased by the Dow-Herriman Pump & Machinery Corporation. As mentioned earlier, the new company was known as the Radium Ore Revigator Company.

Initially, Thomas and the Radium Ore Revigator Company were on good terms. This is evident from the extensive and complimentary coverage that Thomas was given in what I believe was the first brochure for the Revigator (published in 1925). That the relationship was also a financial one is suggested by the fact that Thomas listed himself in the 1925 Long Beach City Directory as the manager for the Radium Ore Revigator Co. located at 420 American Avenue.

It is likely that Thomas even played a role, albeit diminishing one, in the actual manufacture of the Revigator jars. The evidence is the fact that a number of Revigator jars were produced that were identical to the cylindrical Thomas Radium Ore Jars. They were probably produced in late 1924, using Thomas’s manufacturing facility. This might have been necessary if the Revigator company was not yet capable of producing its own jars with the new design, the jars shaped like cooling towers.

This relationship between the Revigator Company and R.W. Thomas seems to have undergone a significant change sometime in late 1925 or early 1926. The 1926 Long Beach City directory lists R.W. Thomas as a sheet metal worker at Thomas and Gunn (2525 east Fifth Street)—no mention is made of the Revigator Company. And what I believe was the second brochure for the Revigator, probably published in late 1925 or sometime in 1926, only gives the following brief nod to our hero: “R.W. Thomas, Radium student and exponent of the Revigator.” The third brochure, the one with the 1928 copyright, doesn’t mention him at all.

Had they parted ways amicably with Thomas receiving a just compensation, or had had Elmer Haslett considered Thomas an unnecessary expense and cut him loose? I don’t know.

Ralph and Charlotte Thomas and the Radium Cones

In 1926, as mentioned previously, Thomas was operating a sheet metal shop in Long Beach, California. Unfortunately, the business didn’t last more than a couple of years. The last reference to the Thomas and Gunn sheet metal operation was in the 1927 Long Beach City Directory.

By 1928 Thomas’s occupation had changed to electrical sign repair, at least according to the city directory. The new business was located at 138 American Avenue while his residence was identified as 411 East Fourth Street. Interestingly, the 1928 directory listing includes the name of his wife Charlotte. This is the earliest reference I know of indicating that R.W. Thomas was married.

Sometime toward the end of 1928, Thomas started producing the Radium Cone. The first mention of it that I have found is in an advertisement posted in the December 28, 1928 issue of the Pecos Enterprise and Gusher.

By the following year, 1929, the stock market had collapsed and Thomas was listed in the city directory as an “inventor” (still working at 138 American Avenue). The electrical sign repair business seems to have been even less profitable than sheet metal work. Then again, perhaps Thomas had decided to focus his efforts on his new Radium Cone Company.

Thomas’s situation didn’t seem to change much in 1930, although I suspect that his finances might have worsened. That year’s census indicates that R.W. Thomas and his wife Charlotte had taken in a lodger, probably to help make ends meet. Elmer Haslett was also sharing his home—to Genevieve Marquis, a 22 year old French maid.

The noteworthy thing about the 1931 Long Beach City Directory was that it included a separate listing for the Radium Cone Company:

“RADIUM CONE CO (R.W. Thomas), Live Fresh Water Charged With Radium Emanation Now Called Ultra Violet Rays or Vitamin D. 138 American Av, Tel 624-61.”

In 1932, a few more products were added to the listing:

“RADIUM CONE CO (R.W. Thomas), Mfrs of Radioactive Water Cones, Radio-Active Devices for Cosmetics, Skinglo Lotion. 138 American Av, Tel 624-61.”

Alas, 1932 was an unfortunate year for Mr. and Mrs. Thomas. Ralph passed away August 31 and left Charlotte in charge of the business. For one reason or another, she and the Radium Cone Company would no longer be listed in the City Directory (although I believe that she still lived in Long Beach). The “disappearance” from the directory might have been related to the seizure by federal authorities of 19 packages of Radium Cones that Charlotte had shipped on January 30, 1933 to a distributor in Phoenix, Arizona.

Despite the seizure, Charlotte would continue to sell Radium Cones throughout the 1930s. However, in 1936 she had to agree to a Federal Trade Commission stipulation that she cease and desist from making any medical claims about the cones (FTC Decisions Volume 23, case 1786, August 7 1936). In other words, she could sell the cones, but not suggest in any way that they would help alleviate medical disorders.

The figure to the right shows a Thomas Radioactive Cone. Since the same molds were probably used for the Radium Cones and the Thomas Cones, their appearance should be identical. Read more about Thomas Radioactive Cones.

The Radium Cone Company changed its name to the Thomas Radioactive Cone Company sometime around 1935. Perhaps this was Charlotte's way of honoring her late husband. The Thomas Cone Trade Mark was registered Oct. 22, 1935 (No. 329287). About the same time, the company moved from Long Beach to Inglewood.

Oddly enough, the next seizure of the Thomas Cones by federal authorities, a small shipment to Shreveport, Louisiana, occurred because Charlotte had provided too little information about the product. Instructions for using the cones were not provided. Their ingredients were not specified. Not even the identity of the manufacturer was given. The referred to seizure occurred in March of 1940 (see Federal Drug Administration Notices of Judgement. Case 331, March 1942).

In the early 1940s, Charlotte sold the Thomas Radioactive Cone Company to Earl T. Pribble, a long-time distributor in Lubbock Texas. Pribble continued to produce the cones into the 1950s, and possibly the early 1960s. When he died in 1963, the cones had been in continuous production for close to 30 years.