Pocket Dosimeters (direct-reading)

Pocket Chambers and Pocket Dosimeters

Paul Frame, Oak Ridge Associated Universities

Pocket chambers and pocket dosimeters are small ionization chambers that, as the name implies, are usually worn in the pocket. While they were designed to measure X-rays and gamma ray exposures, they would also respond to betas above 1 MeV. Neutron-sensitive versions were also available. The terms pocket chamber and pocket dosimeter are often used interchangeably. The original distinction between the two terms, used here, is rarely made anymore. In part, this is due to the fact that the devices that I call pocket chambers are rarely used any more.

1. Pocket Chambers

Pocket chambers go by a variety of names: indirect-reading dosimeters, non-self-reading dosimeters and condenser-type pocket dosimeters. Prior to WW II, they were only used to a limited extent, primarily in medical facilities and around accelerators. The Manhattan Project however created a huge demand and they were worn by almost everyone who might be exposed to radiation.

A pocket chamber acts as an air-filled condenser (capacitor) much like the thimble chambers used in radiology. Prior to being worn, it is given a charge with a charger-reader, e.g., the Victoreen Minometer. Any subsequent exposure to radiation ionizes the air inside the chamber and this reduces the stored charge. In order to quantify the exposure, the charge is measured and the decrease is related to the exposure.

Pocket chambers were approximately 4-5” long and 0.5” in diameter. An aluminum rod (ca. 0.0625” in diameter) running along the chamber axis served as one electrode, while the outer wall of the chamber served as the other electrode. The central electrode was suspended at each end with a polystyrene insulator and at one end it penetrated the insulator to serve as the charging contact. One problem with the early models involved the threaded caps that were used to protect the charging contact—they would wear and the metal fragments would get on the insulator. The graphite coating on the inside of the chamber wall caused a similar type of problem with some of the early models because it would sometimes flake off and short out the chamber. The early models were also susceptible to discharge as a result of mechanical shock because the central electrode would flex and contact the chamber wall. To solve this problem, later versions used a thicker central electrode and/or positioned a small insulating disk in the center of the electrode. Because of these problems, it was usual for a worker to wear two dosimeters and the lower of the two readings was considered the most accurate.

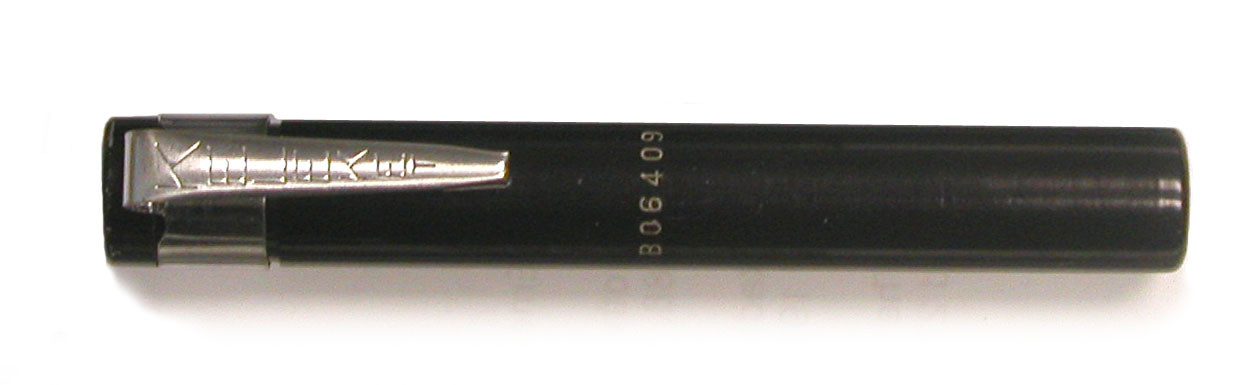

2. Pocket Dosimeters

Like pocket chambers, pocket dosimeters are known by a number of other names, e.g., direct-reading dosimeters, self-reading pocket dosimeters and pocket electroscopes. They are actually quartz fiber electroscopes the sensing element of which is a movable bow-shaped quartz fiber that is attached at each end to a fixed post. The latter is also shaped like a bow (or horseshoe). The dose is determined by looking through the eyepiece on one end of the dosimeter, pointing the other end towards a light source, and noting the position of the fiber on a scale. Until 1950 or so, the vast majority of pocket dosimeters had a range up to 200 mR, although a few high range versions were available for emergency situations. Higher range versions became more readily available in the 1950s for military and civil defense purposes.

Pocket dosimeters tended to be slightly larger than pocket chambers. Their walls might be made of aluminum, bakelite, or some other type of plastic. If the material was not conductive, the inner surface of the chamber was coated with Aquadag (graphite). The central electrode was usually a phosphor bronze rod. This made pocket dosimeters more energy dependent than pocket chambers whose central electrodes were usually aluminum. Some dosimeters (e.g., Keleket Model K-145) employed boron-lined chambers which made them sensitive to thermal neutrons.

Pocket dosimeters must be charged (ca. 150 – 200 volts) with some sort of charger, but they do not require another device to read them. This allows the worker to determine his or her exposure at any time, an important advantage when working in high radiation fields.

The first direct reading pocket dosimeters were built by Charlie Lauritsen at the California Institute of Technology.

3. Pocket Chambers (indirect-reading) vs Pocket Dosimeters (direct reading)

- Pocket chambers were far less expensive (ca. $5 vs $40 in 1950).

- Pocket chambers, despite their problems, were more reliable.

- Pocket chambers did not permit the wearer to know their exposure, for military purposes, this was sometimes desirable.

- Pocket dosimeters allowed the worker to check their exposure during a particular task and to take corrective actions when appropriate.

- Pocket dosimeters did not have to be recharged every time they were read.

- Pocket dosimeters could use very small chargers, small enough to easily fit into a pocket.

References

- Campbell, D.C., Radiological Defense Vol. IV, Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, 1951.

- Davis, D.M., Gupton, E.D. and Hart, J.C. Applied Health Physics Radiation Survey Instrumentation ORNL-322 (1st Rev.), January 1954.

- Morgan, K.Z., Health Control and Nuclear Research, unpublished manuscript, ca. 1951.

-

Bendix Model 609 Neutron Pocket Dosimeter Bendix Model 609 Neutron Pocket Dosimeter

-

Bendix Pocket Dosimeters Bendix Pocket Dosimeters

-

Bendix Prototype Ratemeter Bendix Prototype Ratemeter

-

Keleket K-112 Pocket Dosimeter Keleket K-112 Pocket Dosimeter

-

Keleket K-191 Pocket Dosimeter and Two Unknown Keleket Models Keleket K-191 Pocket Dosimeter and Two Unknown Keleket Models

-

Landsverk Pocket Dosimeters, Models L-49, L-50, L-51, L-53 Landsverk Pocket Dosimeters, Models L-49, L-50, L-51, L-53

-

Model BM 20020/10 Cambridge Pocket Dosimeter Model BM 20020/10 Cambridge Pocket Dosimeter

-

Model PD-200 Riken Pocket Dosimeter Model PD-200 Riken Pocket Dosimeter

-

Shonka Pocket Dosimeter Shonka Pocket Dosimeter

-

Tracerlab SU8 Pocket Dosimeter Tracerlab SU8 Pocket Dosimeter

-

Victoreen Model 541 Direct Reading Pocket Dosimeters Victoreen Model 541 Direct Reading Pocket Dosimeters

-

World's Oldest Direct Reading Pocket Dosimeter World's Oldest Direct Reading Pocket Dosimeter