Radium dial workers painting clock faces with radioluminescent paint, public domain photo - Wikimedia Commons

It was a national scandal what happened to the “Radium Girls” in the 1920s.

Radium was discovered by Marie and Pierre Curie in 1898, and its unique glow and supposed curative powers quickly captivated public imagination. By the 1910s and 1920s, radium was being used in a variety of products from cosmetics to health tonics. The April 1920 issue of Scientific American called out these items as containing radioluminescent paint: house numbers, keyhole locators, ship's compasses, telegraph dials, mine signs, poison bottle indicators, theater seat numbers, luminous fish bait, and glowing eyes for toy dolls and animals.

One of the most popular applications was in the production of luminous watch and clock dials, allowing people to read the time in the dark! The same Scientific American magazine article noted more than 4 million watches and clocks with glowing features had been produced. Factories sprang up throughout the United States, and the workers were predominantly young women who were tasked with painting tiny numbers on the watch faces using radium-infused paint.

At the time they were employed, the Radium Girls were considered relatively well-paid compared to many other jobs available to women. The work was considered skilled labor, and the wages reflected that. The job was coveted because it was a good option for a factory position: it was clean, the labor was easy, and it was prestigious because of the supposed health benefits of working with radium.

Image of the workers at Radium Dial Company, Photo Credit: AP Photo/Ottawa Daily Times

There were a few methods the radium dial painters used to apply the paint: painting it on with a brush, painting it with a pen or stylus, applying it with a mechanical press, and dusting (which involved dusting a freshly painted dial with radioluminescent powder so it would stick to the paint).

By the mid-1920s and into the 1930s, a rash of radium-related illnesses began to emerge including hundreds of instances of severe anemia, radiation poisoning, bone fractures and necrosis of the jaw, a condition that came to be known as “radium jaw.” The common denominator in these cases: the sick had worked as radium dial painters.

How did they get sick? In pursuit of beautiful penmanship for the watches and clocks they worked on, many of these women would use their mouths to put a point on the brush as they painted—ingesting radium-laced paint as they did so. Dial painters were assured this practice was safe and the radium would simply pass through their digestive track. An article in the National Archives spells out the actual danger: “radium’s properties are similar enough to calcium that it can be incorporated into bones, gradually killing the tissues and affecting the blood.”

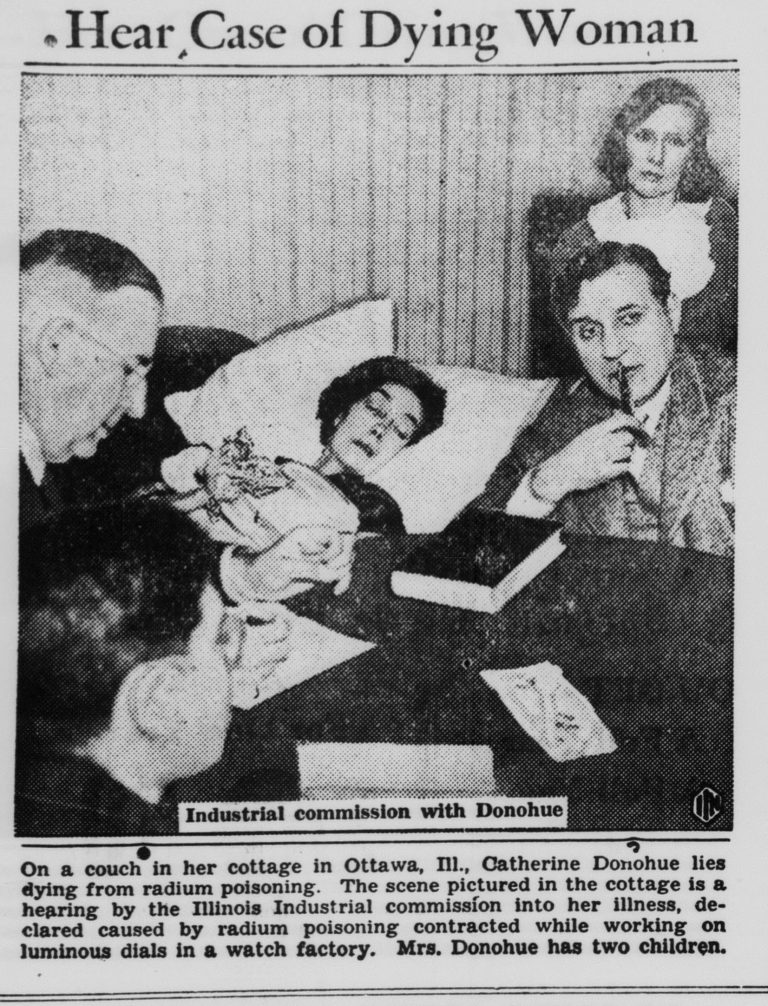

Newspaper clipping from the Worcester Democrat and Ledger-Enterprise (Pocomoke, MD, March 4, 1938) Credit: Library of Congress

It’s worth noting that lip-tipping the brushes was not something the dial painters just decided to do on their own. At least in some plants, they were actually trained how to do it, if not encouraged to do it. In fact, the instructors sometimes swallowed some of the paint to show it was harmless. It has been estimated that a dial painter would ingest a few hundred to a few thousand microcuries (uCi) of radium per year. While most of the ingested radium would pass through the body, some fraction of it would be absorbed and accumulate in the skeleton.

Catherine Donohue was one of these Radium Girls, who worked at the Radium Dial Company in Ottawa, Illinois. She’s considered instrumental in bringing attention to the plight of the radium dial painters. Despite facing severe health challenges, she and some colleagues pursued legal action against their employer, who denied liability, leading to increased public awareness and changes in legislation. Radium Dial Company and others in the industry initially disputed claims that the health issues were related to the work conditions or the radium paint used in their factories. The reluctance to take responsibility led to significant legal battles. Donohue’s family eventually won modest compensation after lengthy arbitration. She died in July of 1938 at the age of 35. The final legal victory came in October of that year.

Robley Evans, Ph.D., Credit: Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Health physics Professor Robley Evans, Ph.D., focused much of his research at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) on radiation’s effect on the human body. Because it was such a big scandal, he studied what happened to the radium dial painters and explained his findings:

“For wiping and tipping the brush the workers found that that either a cloth or their fingers were too harsh, but by wiping the brush clean between their lips the proper erasing point could be obtained. This led to the so-called practice of ‘tipping’ or pointing the brush in the lips. In some plants the brush was also tipped before painting a numeral. The paint so wiped off the brush was swallowed."

Evans’ extensive research proved instrumental in establishing safety standards for radium handling and contributed significantly to laying the groundwork for worker protections. He established a maximum permissible body burden for radium of 0.1 uCi. Remember, uCi are microcuries. Think of a curie as a whole cake and a microcurie as a crumb of that cake. It’s a small, precise measurement, and it helps us understand how dangerous tiny amounts of absorbed radium can be. To put that into perspective, if the estimates are correct, and the radium dial painters ingested a few hundred to a few thousand microcuries, their exposure was as much as nearly 20 thousand times the maximum permissible body burden. This comparison starkly illustrates the severe overexposure the workers experienced compared to what is now understood to be safe levels of radium exposure.

Ultimately, the Radium Dial Company ceased operations. In the aftermath, industry practices faced a great regulatory impact. Though agencies like the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the Environmental Protection Agency came along after the peak of the radium dial painter cases, their stories influenced what would eventually be established for workers’ health and safety.

This wristwatch is engraved with the year 1927. It has radioluminescent paint. See it in ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity is proud to have relevant items on display.

This watch from 1927 isn’t in great shape, but it has radium-containing radioluminescent paint.

And, Robley Evans may have begun his investigation into the effects of radium on the body in the 1920s, but his research into this field continued for decades. Among the items museum visitors may see include personal tools Evans used to help radium-industry workers.

Robley Evans’ ion chamber and glass flask used for the analysis of breath samples from workers in the radium industry are on display in ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

Sources: