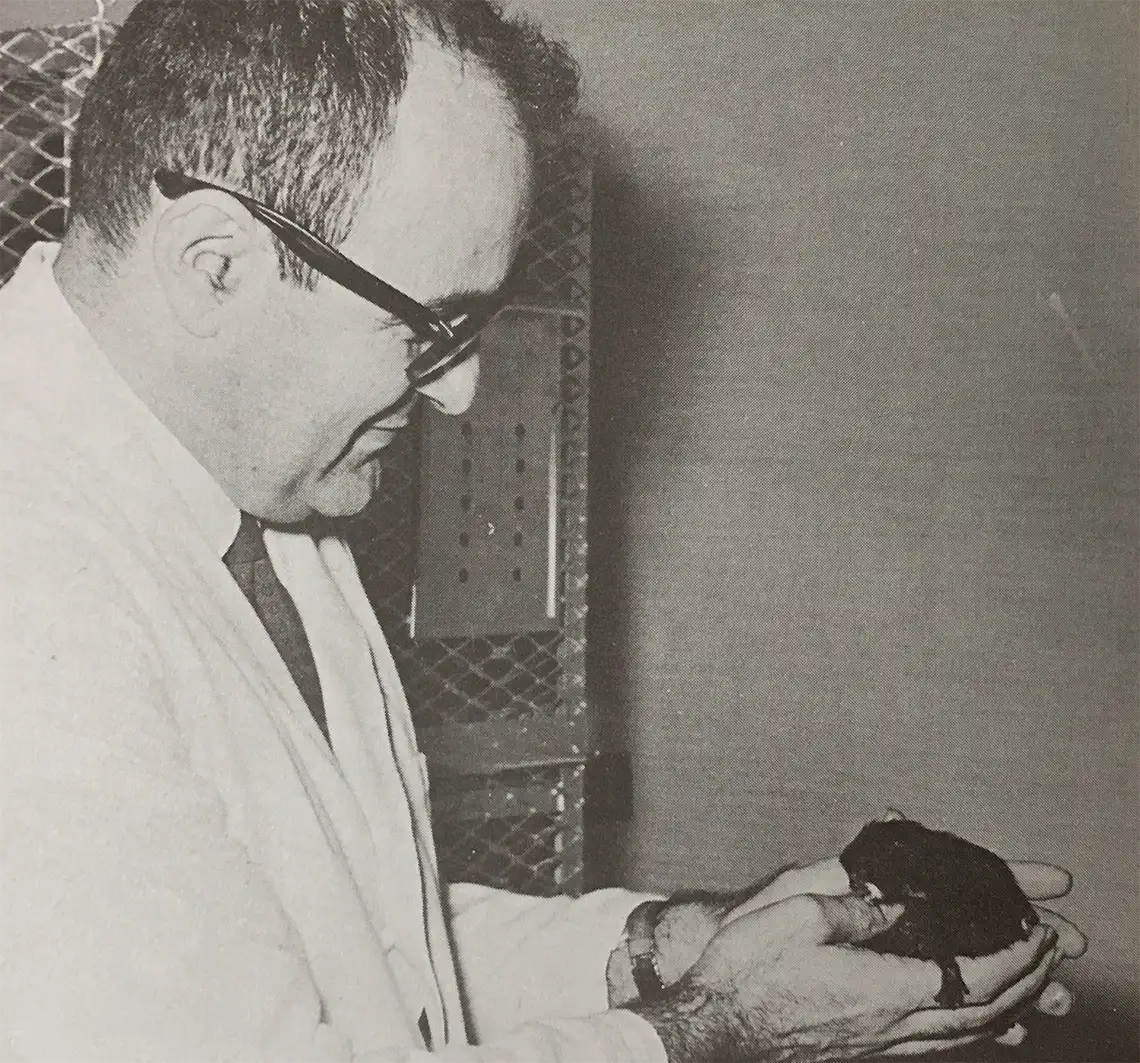

Dr. Gengozian with a marmoset

What’s with the monkeys in ORAU’s history? How did this government contractor come to establish a fruitful research program involving primates?

Chief Scientist Nazareth Gengozian, Ph.D.,—who worked for ORAU’s predecessor ORINS—blazed a new trail when he established a colony of South American marmosets in Oak Ridge, Tenn., for his research supporting the Atomic Energy Commission in 1961. Gengozian had been working as a biologist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) studying irradiated mice in the Mammalian Recovery program to find potential therapeutic value of marrow infusions when he made the move across town to become ORINS’ chief scientist. In his new role, he was able to use what he learned at ORNL because he was tasked with developing a basic marrow transplant program. He wanted to explore the feasibility of performing transplants in patients with hematologic malignancies (that is, cancers that begin in the cells of the immune system or in blood-forming tissue, such as bone marrow).

Because of his years of studying the effects of ionizing radiation on immune processes, Dr. Gengozian was a leading expert in this newly forming field of medicine. He had heard about a lab in Miami studying marmosets to learn about nutrition, so he got the greenlight to study the same primates to learn about transplant immunology. What he found moved cancer research forward in significant ways.

Why marmosets?

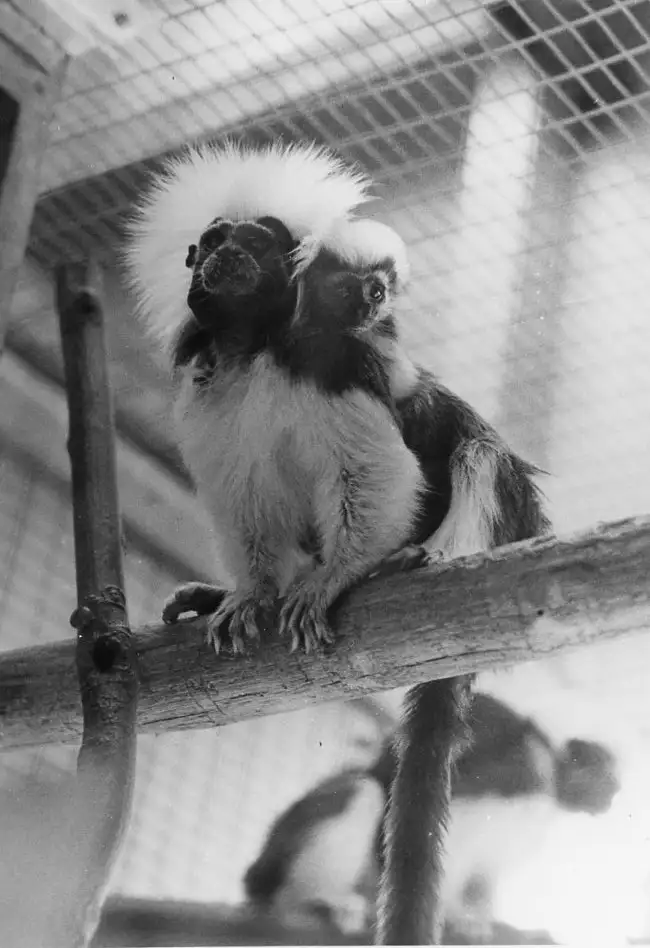

The research value in marmosets lies in the fact that marmosets are the only non-human primates that regularly produce fraternal twins (with a high frequency of 80-85%!). In utero, the twins exchange tissues and develop natural tolerance to the foreign tissue of the other. This aided understanding of the markers in our bodies that recognize which cells belong in our body and which do not. From here, doctors realized the importance of white blood cell testing and histocompatibility (so that the recipient’s body doesn’t reject cells or tissues from a donor).

Gengozian holds a pair of marmoset twins.

A set of studies showed that animals successfully transplanted with marrow genetically different from their own continued to have an impaired immune system. This indicated a critical need for finding the right donors for compatibility. Building on all that they were learning, ORAU’s Medical Division established a cytogenetics laboratory in 1964, and it became a major resource in providing a reliable technique for assessing human total-body radiation injury and chromosome analysis. Primarily, the cytogenetics lab was created to support research on the genetic effects of radiation exposure, providing chromosome analysis services for people who had been exposed to ionizing radiation (like people who worked in the nuclear industry or patients who had undergone radiation therapy). Even though finding the right donors for bone marrow transplants wasn’t the main purpose of the lab, this capability changed the game and greatly improved the success rate of marrow transplantation.

Success and growth

Dr. Gengozian also discovered that radiation delivered over a period of a few minutes was more effective for immunosuppression than the same amount of radiation delivered over the course of an hour. Thus, he developed the immunological basis for bone marrow grafting as we do it today. Previously, doctors attempted bone marrow grafting on very sick patients who were immunosuppressed and defenseless against infection. It was their last resort. They wanted to exhaust conventional wisdom of the time before trying a marrow graft.

Now, physicians know to bring in patients not handicapped by infection for this procedure. Dr. Gengozian’s sequence was to give the patient seven days of immunoglobulin, followed by total-body irradiation, and within a few hours of the irradiation, Gengozian would do the bone marrow graft at a higher dose rate for a shorter amount of time. This led to one of the first successful bone marrow transplants for a leukemia patient.

Cotton-top tamarins, like humans, spontaneously develop colon cancer.

The original intent for the marmoset research was limited, but one success led to another opening the door to more research opportunities. An unexpected finding was that spontaneous colon cancer and acute colitis occurs in cotton-top tamarins (an endangered marmoset species). This is the only known mammal other than humans to develop spontaneous colon cancer. From here, researchers wanted to know if therapy for colitis could also reduce the incidence of colon cancer. It was a worthwhile inquiry that led to some new treatment options for at-risk patients.

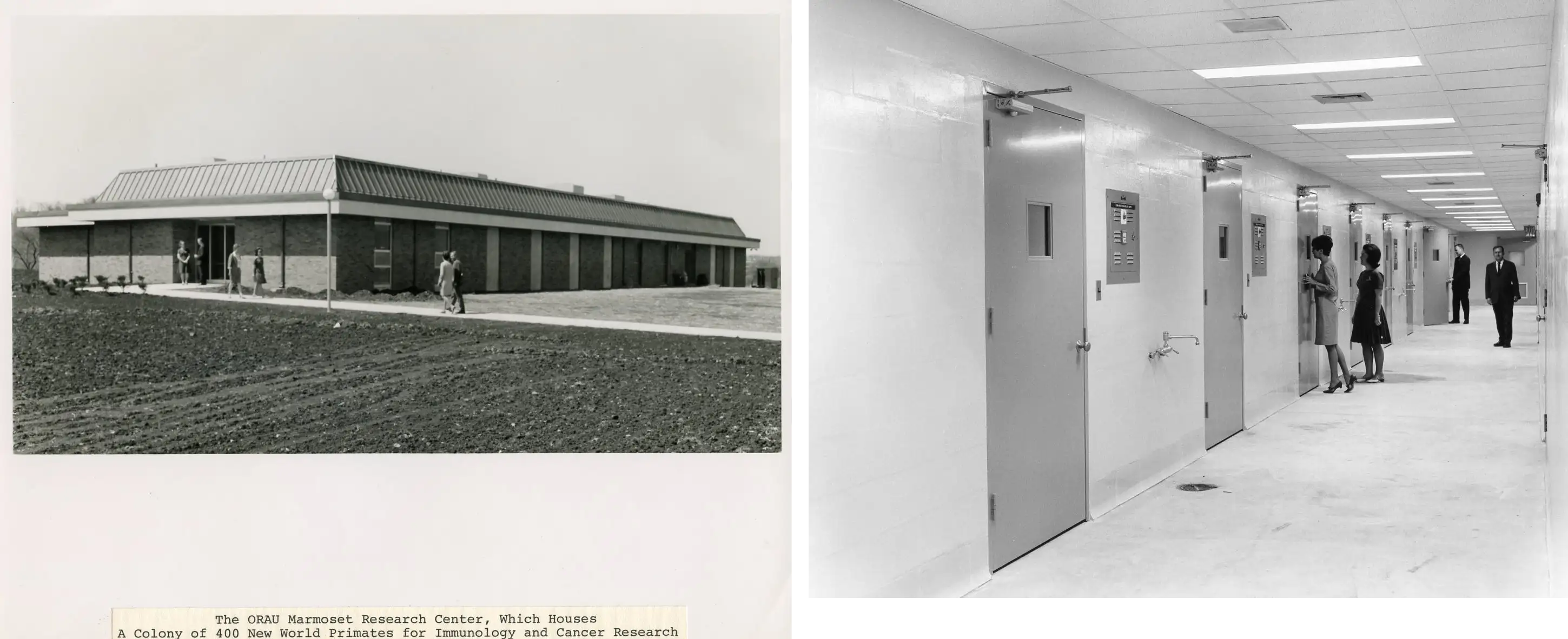

With so much value gained through Dr. Gengozian’s marmoset colony, ORAU built a 10,000-square-foot facility for labs, offices and new space for the colony in 1967. This building could house 450 marmosets in 12 rooms with carefully controlled environments. It was one of the only colonies of marmosets in the United States that was developed for general lab research.

In 1979, ORAU expanded the program again. This time, it was a 2,250-square-foot marmoset breeding facility. Other than behavioral observations, no experimental studies were permitted in this complex.

Transition

By 1980, the marmoset population had grown to almost 400. Even so, federal dollars became tight and Dr. Gengozian lost funding for his program in 1981. This ushered in transition: Gengozian moved to Oklahoma to research monoclonal antibody production, and ORAU’s marmoset colony became a project headed by the laboratory director at the Comparative Animal Research Laboratory (CARL). Researchers like Neal Clapp, Ph.D., and Marsha Henke (pictured here) continued Gengozian’s work.

Dr. Neal Clapp, CARL Director, and Marsha Henke examine a marmoset X-ray.

Though budget woes didn’t dissolve, interest in studying marmosets and tamarins continued, so the program trucked along. In 1988, ORAU took the lead and formed the Marmoset Research Center of Oak Ridge (MARCOR). This was a consortium of universities and industries involved in the biological research of these animals. But, by 1992, the cost of operation wasn’t sustainable. ORAU transferred ownership of the Marmoset Research Center to the University of Tennessee Medical Center. In 1997, the university disbanded the program.

Gengozian’s legacy

Picture of Dr. Gengozian during his tenure at ORAU.

Dr. Gengozian found his way back to East Tennessee in the early 1990s and took a joint position at Thompson Cancer Survival Center and as a professor at the University of Tennessee. He retired at 77. In his 52-year career, Gengozian published 140 research papers, contributed chapters in four books and co-edited a book about primates in experimental medicine. He also served on the editorial board of the journal Transplantation and was an associate editor of the Journal of Medical Primatology. His career had a significant impact on effective cancer treatment as he was determined to find new solutions through his research. Dr. Gengozian died in 2020, but not before he was able to enjoy witnessing the long-term results of his findings in bone marrow transplants, colon cancer treatments and, most recently, successful stem cell options at the Thompson Cancer Survival Center. Thank you, Dr. Gengozian, for your curiosity and your commitment to science. Studying monkeys at ORAU proved invaluable in scientific discovery.