Elizabeth Rona, a nuclear chemist whose contributions to science impacted our understanding of radioactivity, nuclear physics and atomic energy

In the world of science, Elizabeth Rona, Ph.D., was somewhat of a celebrity when she joined the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies (ORINS) in 1950 as a senior scientist in the Special Training Division. The Hungarian-born nuclear chemist had worked with the who’s who of nuclear pioneers including Nobel Prize winners Marie Curie, discoverer of radium and polonium; Otto Hahn, discoverer of nuclear fission; and George de Hevesy, discoverer of radiotracers. But don’t let the rubbing of elbows fool you. Rona was a brilliant mind in her own right. The reason she had the opportunity to work with these notable scientists is because of the timing of her research interests in radioactivity, exceptional expertise in extracting polonium and her contributions to the understanding of radiochemistry.

Upheaval and up-hill battles

Elizabeth Rona came up in a time when women weren’t expected to excel in academia or any male-dominated field, like science. In her book “How It Came About: Radioactivity, Nuclear Physics, Atomic Energy,” Rona said she loved science from her childhood. “In the early 1900s, science was nebulous and not well understood, but it was extremely exciting,” she wrote. She aspired to go into medicine. Her father (a physician himself) was concerned about his daughter having a hard time making it as a doctor, so he pushed her into chemistry and research. Curious about the world, Rona devoted herself to her studies and fell in love. As one of the only women in her class at the University of Budapest, she earned her Ph.D. in chemistry and quickly found work with scientists who were investigating the same phenomena she was.

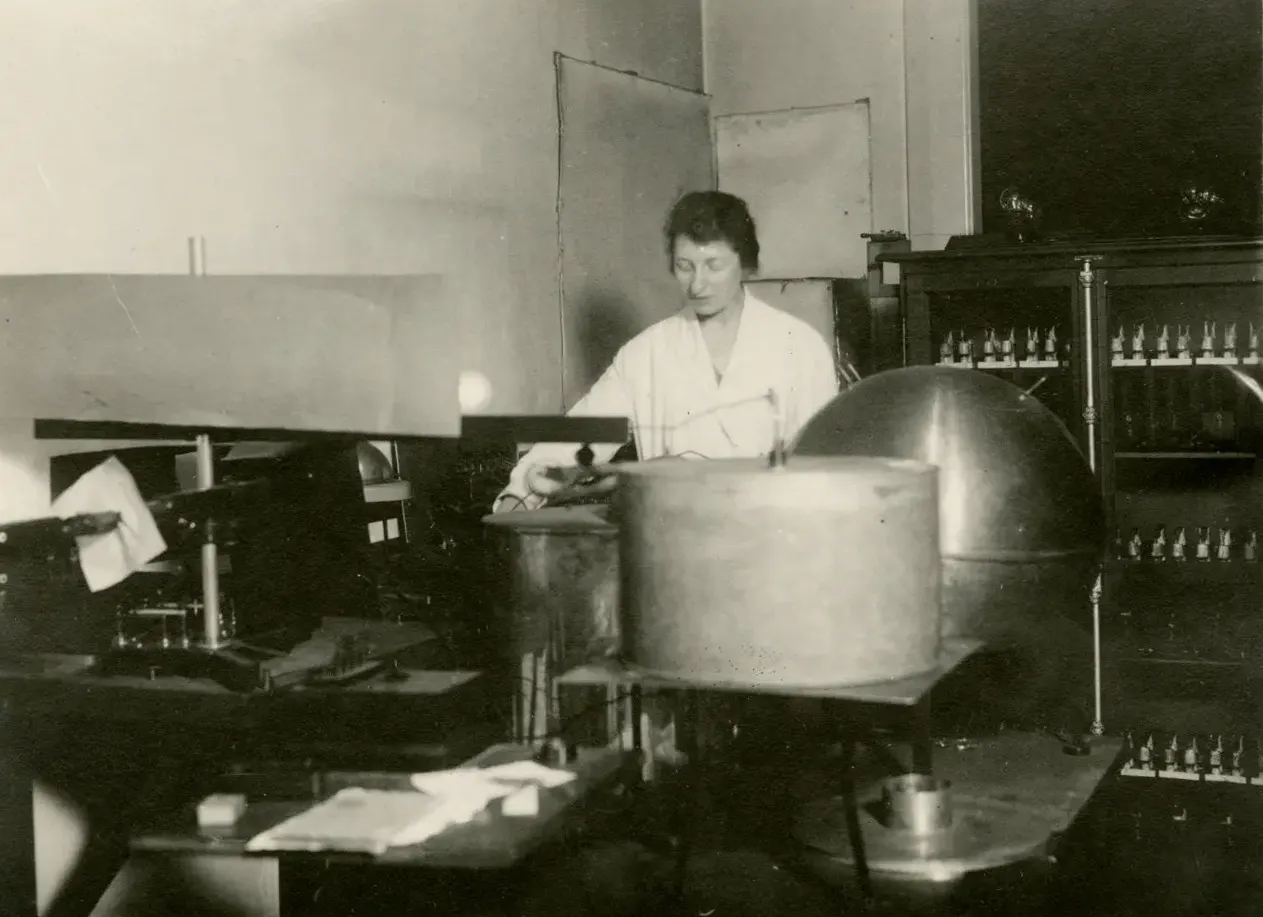

Elizabeth Rona in about 1925 at the Radium Institute in Vienna. Credit: Hans Pettersson Archive/Gothenburg University Library

From tracking the diffusion of radioactive tracers to being a part of the discovery of nuclear fission, Rona moved from lab to lab (often country to country—Germany, Austria and France) as research opportunities became available. Being a woman, she often didn’t receive the credit her male colleagues were lavished with, but Rona kept her head down and focused on learning as much as she could—and the world benefitted!

While working at one lab, she learned how to calculate an atom’s size, which she used to understand its behavior. At another, she worked on making concentrated polonium sources, which proved to be a skill that made her a highly valued scientist. Every stop offered kernels of knowledge, and Elizabeth Rona consumed every morsel.

Rona, seated, with Elisabeth Karamichailova, far right, Berta Karlik, far left, and another scientist at the Radium Institute in Vienna. Credit: Hans Pettersson Archive/Gothenburg University Library

Beyond the nature of her research necessitating a nomad lifestyle, global politics in the post-World War I days were turbulent with antisemitism on the rise. In 1941, Rona, an ethnic Jew, fled Europe and immigrated to the United States. To aid the war against the Nazis, she shared her methods for concentrating polonium with her newly adopted home country. Those methods were employed in building the atomic bomb. As one of many contributors, Rona’s work as a radiochemist in the war effort was effective and celebrated.

Oak Ridge becomes home

After being recruited to work on the top-secret Manhattan Project, Rona stayed on with Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Oak Ridge, Tenn., where she continued her research a few more years. From there, she wouldn’t go far.

When World War II ended, William Pollard, Ph.D., a physics professor at the University of Tennessee, led the establishment of the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies (ORINS, later renamed Oak Ridge Associated Universities) with 14 founding universities that would provide experts to manage research projects for the U.S. government. Seeing the rapidly growing need for professional personnel to be trained in the use of radioactive isotopes, Pollard specifically organized the Special Training Division within ORINS (today, known as ORAU’s Professional Training Programs, one of the organization’s longest enduring programs) for this purpose. ORINS offered a series of courses in basic radioisotope techniques involving both lectures and extensive, hands-on laboratory practice. Pollard hired Elizabeth Rona because she was perfect for this job.

Rona, far left, in Oak Ridge, Tenn., in 1954 with the Swedish physicist and oceanographer Hans Pettersson, his wife Dagmar Pettersson, and an unidentified friend. Credit: Hans Pettersson Archive/Gothenburg University Library

“Dr. Rona’s long experience with radioactivity from the early period of its discovery made her an especially valuable member of the teaching staff for these courses,” Pollard explained. “When in 1954, the courses were opened to foreign participants through President Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace program, her fluency in a number of languages was a valuable additional aid in her teaching.”

Pollard prized Rona and encouraged her to get her thoughts and experiences down on paper. The result was her 1978 book, which was somewhat autobiographical as well as an historical account of the emerging science of the time. “Of special interest is her personal acquaintance with most of the scientists involved in research on radioactivity throughout this long period. This places her in a unique position to tell the story of this chapter of 20th century science. Oak Ridge Associated Universities is pleased to make this memoir of an esteemed member of its scientific staff available in this form,” Pollard wrote in the book’s foreword.

Read How it Came About: Radioactivity, Nuclear Physics, Atomic Energy (.PDF, 6 MB)

Her book is out of print now, but we scanned it and uploaded it so you could read it for yourself: “How It Came About: Radioactivity, Nuclear Physics, Atomic Energy (.PDF, 6 MB).”

In her 15 years with ORINS, much of her study involved measuring the age of ocean sedimentary layers. She’s known for her work on the natural radioactivity of the earth and seawater, which advanced both geology and oceanography. That’s in addition to her reputation as an international expert in radioactive elements!

In ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity, we have some items Rona used in the laboratory during her time at ORINS and in Oak Ridge. See a Frisch Grid ionization chamber, which can be used to distinguish the pulses produced by different radionuclides as well as “rabbits” Rona likely used at the Oak Ridge Graphite Reactor. Rabbits are sample holders/transfer devices that hold radioactive sources. They’re called rabbits because of the pneumatic tube systems (operated by air or gas pressure) typically used in nuclear research and medical facilities to move these items. The name "rabbit" is thought to derive from the speed and efficiency of these systems, much like a rabbit's quick movement. You can see these artifacts online and in the physical collection, housed at The Pollard Center on ORAU’s main campus in Oak Ridge beginning in January 2025.

Left: A Frisch Grid ionization chamber Elizabeth Rona designed. It was built at ORAU in 1959. Right: Elizabeth Rona’s rabbits she likely used at the Oak Ridge Graphite Reactor. These items can be seen in ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

Legacy

Though she worked alongside a handful of scientists who received Nobel Prizes, Elizabeth Rona was largely undecorated. She dedicated more than six decades of her life to the advancement of science. She died in 1981 at the age of 91. Now that we’re able to step back and see the totality of her contributions as a pioneer in early scientific work that has led to the modern fields of atomic and nuclear physics and oceanography, it’s clear she’s due more recognition.

In 2015, she was posthumously inducted into the Tennessee Women’s Hall of Fame, and a January 2020 New York Times article included Elizabeth Rona in its “Overlooked” series—a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths went unreported in The Times. It’s a start. For a scientist who had to fight for the right to be in the room (as a woman) and the right to exist (as an ethnic Jew), perhaps Elizabeth Rona’s greatest courage is demonstrated in her tenacious curiosity to continue exploring. Her contributions to science came during the most consequential chapter of radioactivity, nuclear physics and atomic energy to date.