Born in Strigeau, Germany, in 1934, Karl Franz Hubner, M.D., came to the United States—specifically, Oak Ridge, Tenn.—to learn as much as he could about nuclear medicine. As an ambitious med student of the early 1960s, he became interested in hematology, or the study of blood and blood disorders, and bone marrow transplantation, which was a brand-new therapy at that time. According to Hubner, it was rumored that doctors in Oak Ridge would soon be attempting bone marrow transplants after the 1958 criticality accident at the Y-12 nuclear plant that exposed eight men to potentially lethal doses of radiation. For a young doctor eager for hands-on experience, Hubner found an opportunity with the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies (ORINS), and he applied for and accepted a nuclear medicine residency position in 1962. ORINS was later renamed to ORAU.

In an oral history interview he gave in accordance with the Department of Energy’s Openness Initiative during the Clinton administration, Dr. Hubner explained the easy decision to move abroad like this: “It was all there in Oak Ridge—the basic biology, radiation biology and hematology in this small clinical unit.”

That unit Huber referred to was known as the ORINS Medical Division.

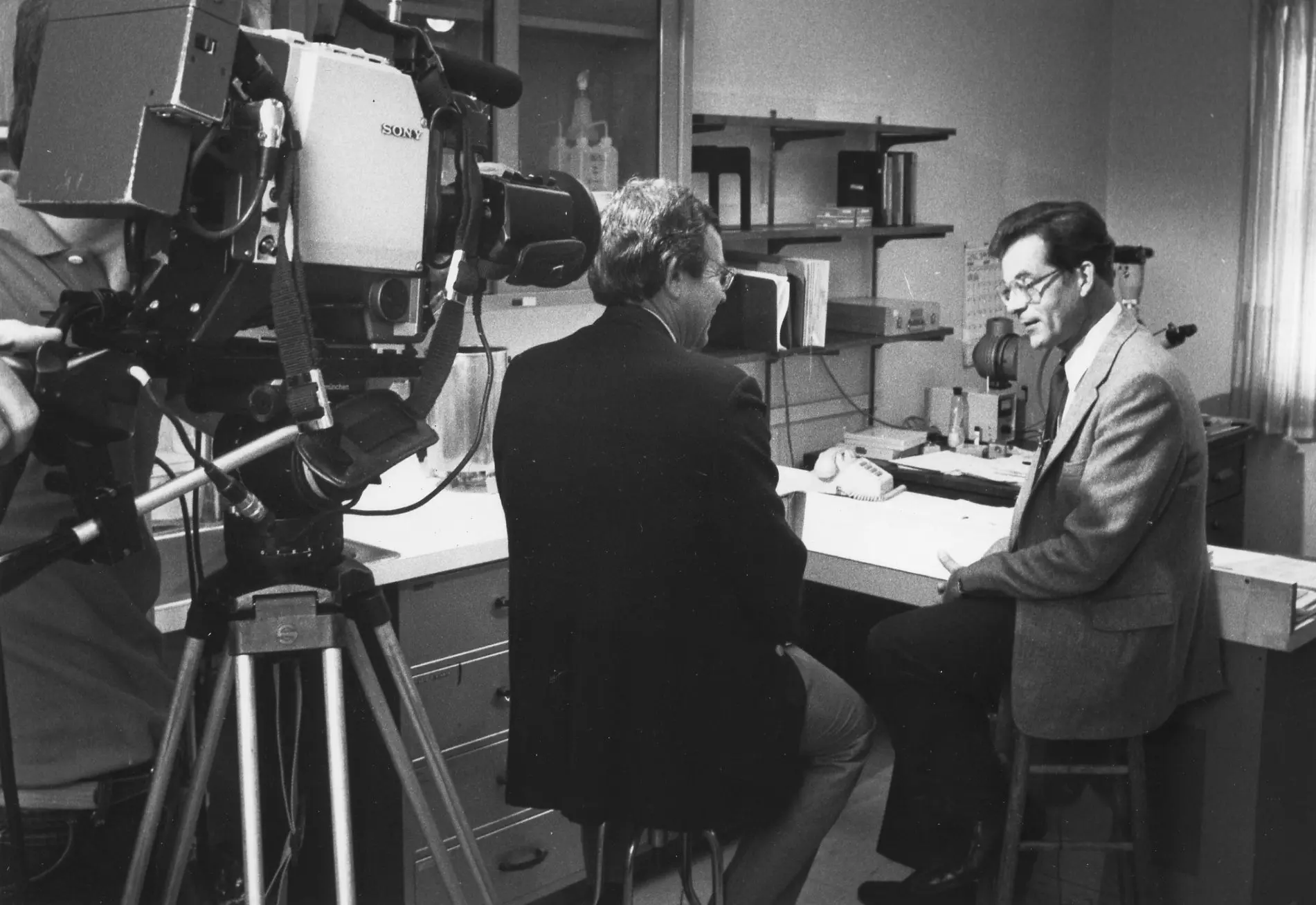

Hubner (right) was interviewed for the Department of Energy Openness Initiative.

‘The cradle of nuclear medicine’

ORINS was operating one of only three hospitals established by the Atomic Energy Commission to explore the use of radiation in cancer treatment. Physicians and scientists in that Medical Division worked tirelessly to develop equipment and techniques for the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. Because many of the most brilliant minds, who were inclined to learning nuclear medicine, had converged on Oak Ridge, this East Tennessee town was the location that had some of the best technology (including prototypic equipment) and training opportunities with some of the most innovative doctors in the world. Through this opportunity with ORINS, Hubner enjoyed practical experience in dosimetry, radiopharmaceuticals, hematology, oncology and tomography.

“Some people call [Oak Ridge] ‘the cradle of nuclear medicine’.” Hubner said in his interview, as he spoke of working alongside the pioneers of the field. In those days, there really wasn’t a set curriculum for people who were studying nuclear medicine, but many people who did want to learn it, came to Oak Ridge to learn from the experts at ORINS. “One of the missions of the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies was to train people in the applications and the use of radionuclides in industry, agriculture, research and chemistry. Nobody had that experience,” he explained. “[ORINS] had these courses that trained thousands of people in the use of radionuclides.”

Exposure to all the education, brilliant scientists and novel opportunities in nuclear medicine left Hubner wanting more. And, as it turned out, ORINS was not quite ready to do bone marrow grafts during his two-year stint. With that unfinished business, Hubner returned to Germany when his residency at ORINS came to an end.

Dr. Hubner’s headshot during his tenure with ORINS

Meanwhile in Germany

Back in Germany, Hubner practiced pediatric cancer therapy; specifically, he focused on cases of leukemia and immune deficiency syndromes. He devoted himself to this cause for three years, and it was this work that sparked his interest in developing methods for detecting cancer as well as measuring the patient’s response to treatments.

Unfinished business

Looking for an opportunity to return to ORINS, Hubner got his chance in 1967 when a position opened for an experimental immunology research assistant. He took the occasion to make Oak Ridge his permanent home. This new role placed Dr. Hubner in the position to participate in cancer therapy research involving total-body irradiation and bone marrow transplantation. Unfinished business: finished. And those early bone marrow transplants that Dr. Hubner participated in served as a foundation for doctors around the country (and the world) to use in their own cancer treatment programs.

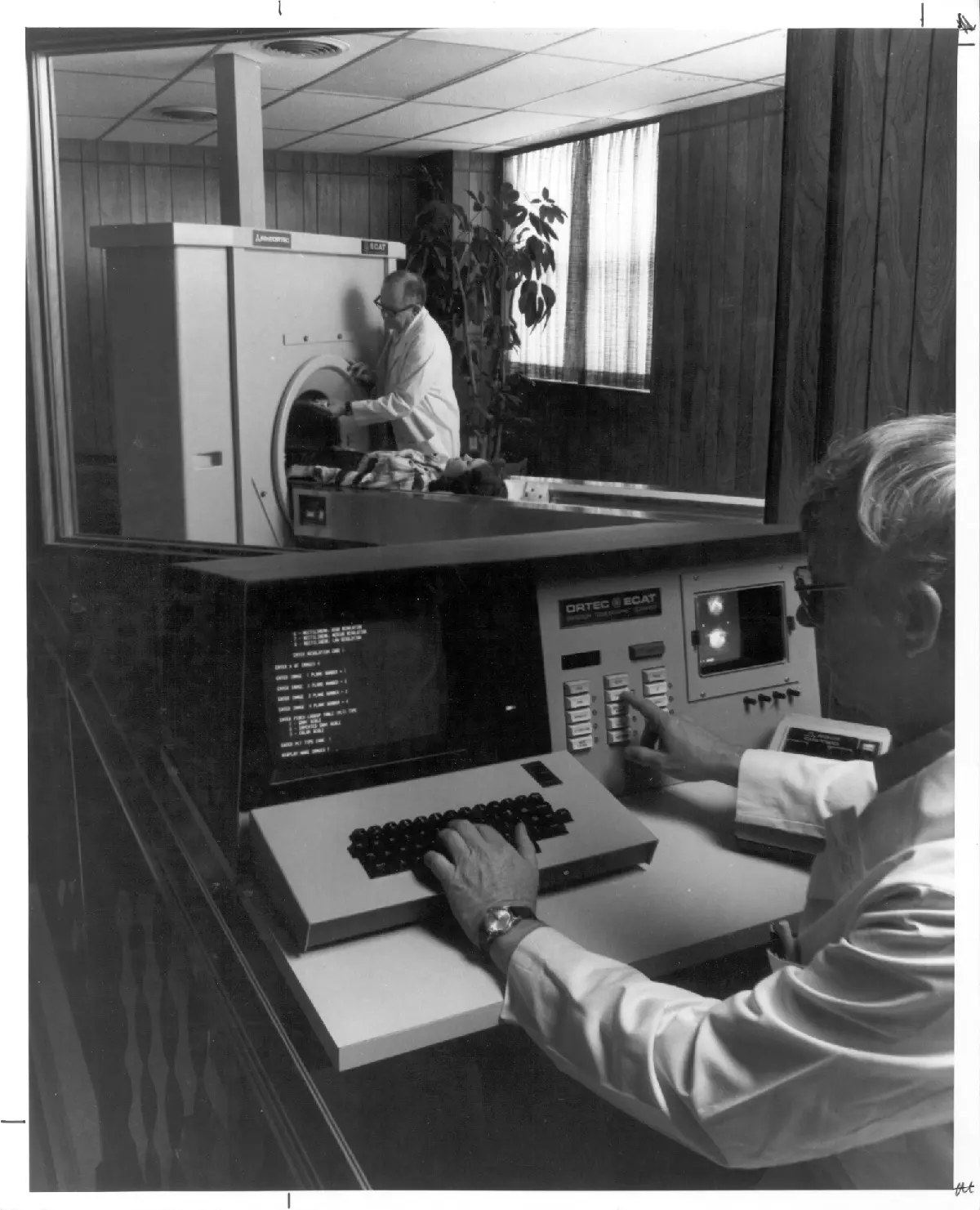

Even as Hubner made the move to the States, he thought he was ultimately going to be a pediatric hematologist and oncologist. After all, the reason he wanted to be in Oak Ridge was to do bone marrow transplants; but now, he was also intrigued by the detection of soft tissue tumors with X-rays and radiotracers. So, he started leaning more into imaging. He was in the right place at the right time because he was on the team that worked to develop whole-body scanners (teletherapy machines that focused beams of radiation on diseased tissue) and the Emission Computerized Axial Tomography (ECAT), a precursor to modern-day Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scanners.

Picture of the ECAT Scanner.

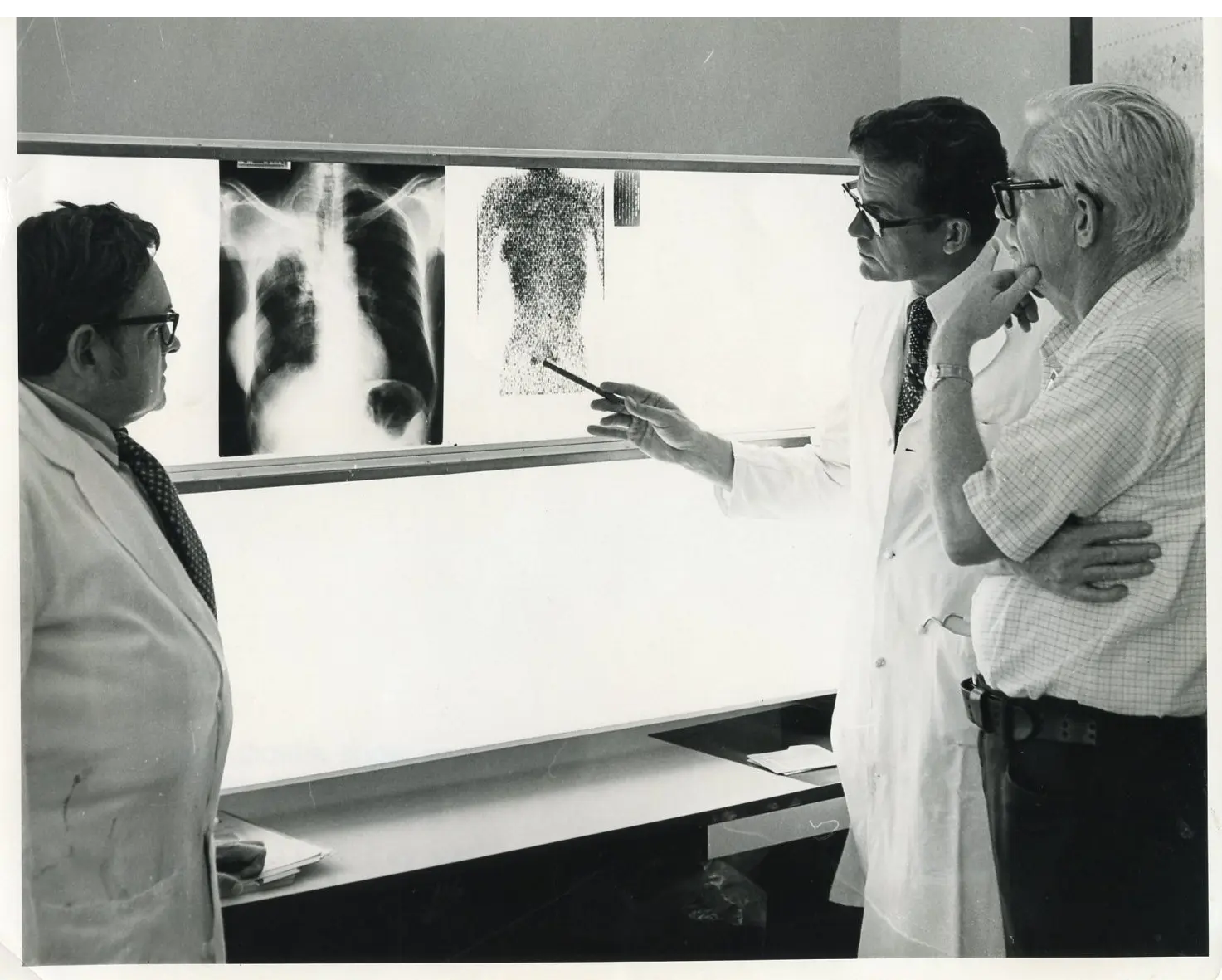

Dr. Hubner is pictured with ORAU’s Center for Epidemiological Research team in the mid-1970s.

In 1970, Hubner was promoted and joined the clinical staff of the ORAU (ORINS’ new name) Medical and Health Sciences Division. In 1977, the Department of Energy gave ORAU a grant to purchase one of the first commercially available PET scanners. That same year, Dr. Hubner was named ORAU’s director of the newly established Radiation Emergency Assistance Center/Training Site (REAC/TS).

Dr. Hubner pictured in his office.

NOTE: After 1992, REAC/TS became part of the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education, which ORAU manages for the Department of Energy.

Shift to imaging

Hubner held this position for five years before he accepted an offer in 1982 to renew the nuclear medicine program at the University of Tennessee Medical Center. In his oral history interview, Dr. Hubner emphasized how proud, that in this role, he was able to open the first clinical PET center in the country. Ever the pioneer, Dr. Hubner always wanted to explore the next frontier of nuclear medicine. Even when he moved on to focus on imaging and the application of radio pharmaceuticals, Hubner consulted with REAC/TS until 1990. His contributions to ORAU and the field of radiation medicine are significant, and he will always be revered for his tenacity to explore bone marrow transplantation and new scanning technologies.

A Legacy That Came Full Circle

At the end of his life, it was the very technology that Dr. Hubner developed that detected his own bone cancer. He died just a few weeks shy of his 90th birthday in January 2024.