Evelyn Watson

It’s a workplace Cinderella story. Evelyn Watson’s career journey is one that is fun to share, and it’s important to ORAU’s history. Watson was a self-taught nuclear scientist who retired with two lifetime achievement awards, but until her early 30s, Watson had no scientific ambition. She was an English major who didn’t set out with determination to climb the ladder. But along the way, that’s exactly what happened.

Evelyn Watson’s beginning

Born in Corbin, Ky., Virginia Evelyn Egner was a bright child with a lot of energy. Her mother taught her to read, write and spell by the time she was four years old. She attended a two-room elementary school and skipped 7th grade. She passed the 8th grade exam, so she went on to high school. Evelyn Egner graduated high school as the valedictorian at 15 years old and went on to college with scholarships. Though she was encouraged to pursue math and science, she loved English (literature and grammar, specifically) and graduated from the University of Kentucky an English major in 1949.

She took a teaching position in a coal-mining town and was then offered an office manager role for the school system. As she worked in the office, she met a young man named Earl Watson who worked in Oak Ridge, Tenn. When she fell in love and married him, she moved to Oak Ridge in 1954. This new chapter ushered in the best kind of transformation: her new town became her beloved home, and she relished her role as a wife and (not long after) a mother.

She needed a job

When Watson was pregnant with her second child, she started thinking about going back to work. In the mid-1950s, finding work as an expectant mother was a tall order. She was turned down from even applying at some places, so she was resigned to the idea of staying home. That’s when she heard about a place called Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies (ORINS), and she was hired there as a record clerk in the purchasing office.

Watson admits she grew restless in this role and quit after nearly two years, but then her husband who had been working at the K-25 plant was laid off. So, she went to inquire about unemployment. She was advised to go back to work at ORINS. Watson didn’t think they’d re-hire her, but they did.

This time she was a clerk in the Special Training Division, and this time she was only there for about a month before she left. She didn’t leave ORINS—just the Special Training Division. The Radiation Safety Officer, Roger Cloutier, had seen Watson’s resume and he wanted her to come work on his team. In an oral history interview through the Oak Ridge Public Library’s Digital Collection, Watson recalled: “He had looked at a lot of different applications, but he had read mine and he thought it was funny because one of the people who recommended me said I was a good cattle judge. Which I was. We had cattle, and I was a judge at fairs and so on. And he thought that was amusing. Also, he was interested in the fact that I’d had quite a bit of chemistry and math, and so he wanted me to go to work for him. So, I did. Now, that turned around my life. Completely turned my life around.”

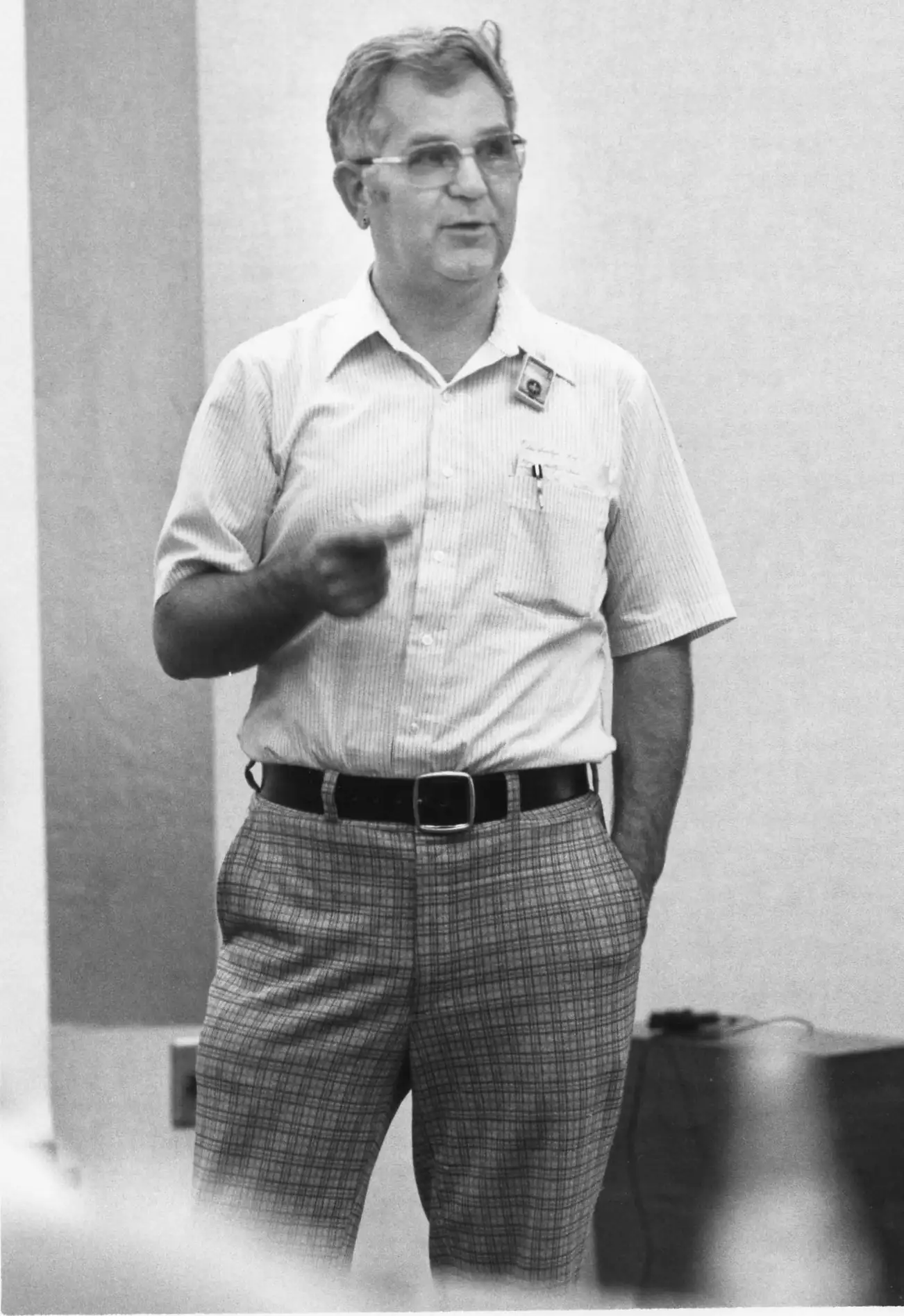

Roger Cloutier

A proper scientist

Essentially, Roger Cloutier recognized Evelyn Watson’s intellect and “stole” her for the Radiation Safety department. Under Cloutier’s mentorship, Watson began a career in radionuclide dosimetry in 1961. When Watson started her new position, she worked in the Medical Division, and her tasks were unlike anything she’d done before. Cloutier gave her smears to review to determine if there was radioactive material in the sample. Watson said it was interesting and fun. In the oral interview, she explained that Cloutier would be on his way to a project and would pause long enough to give her an assignment. “Over his shoulder, he would give me some instructions,” Watson lowered her voice to a whisper before she continued, “and I didn’t have any idea what to do. But, I had some very fortunate things going for me.”

She credited the great resources of the doctors, nurses and technicians at the Medical Division as well as Cloutier’s “library annex” she consulted when she had questions. Cloutier piled books on her desk, and she studied them. “He had books on everything. So, if I couldn’t figure it out, I could go find a book and read on it and work on it,” Watson explained.

Evelyn Watson in the office

Then, as computers came onto the science scene, Cloutier put Watson in courses to learn how to use these new machines. Watson believed those opportunities enhanced her math abilities a great deal. As she sharpened her skills and grew her understanding of nuclear science, Watson became a research associate and lab tech in ORINS’ Radiation Safety office. She even did postgraduate work in the field of radiation dose assessment at the University of Tennessee.

Later, as Watson’s granddaughter, Jayme Evelyn Watson, reflected on her grandmother’s life, she said the English major and mother of two had become a proper scientist.

Succeeding her mentor

The 1960s was the right time to be in radiation research. The nuclear medicine field was growing, and new radioactive materials were being used in patient treatment plans. Cloutier enrolled in every learning opportunity and brought Watson along with him. Many times, the ORINS Medical Division would host these courses. As they taught physicians how to do dosimetry (that is, the science used to determine radiation dose by measurement and/or calculation), the Atomic Energy Commission and the Food and Drug Administration took notice and asked them to set up an internal dose information center, so doctors across the country would know how to administer the best care.

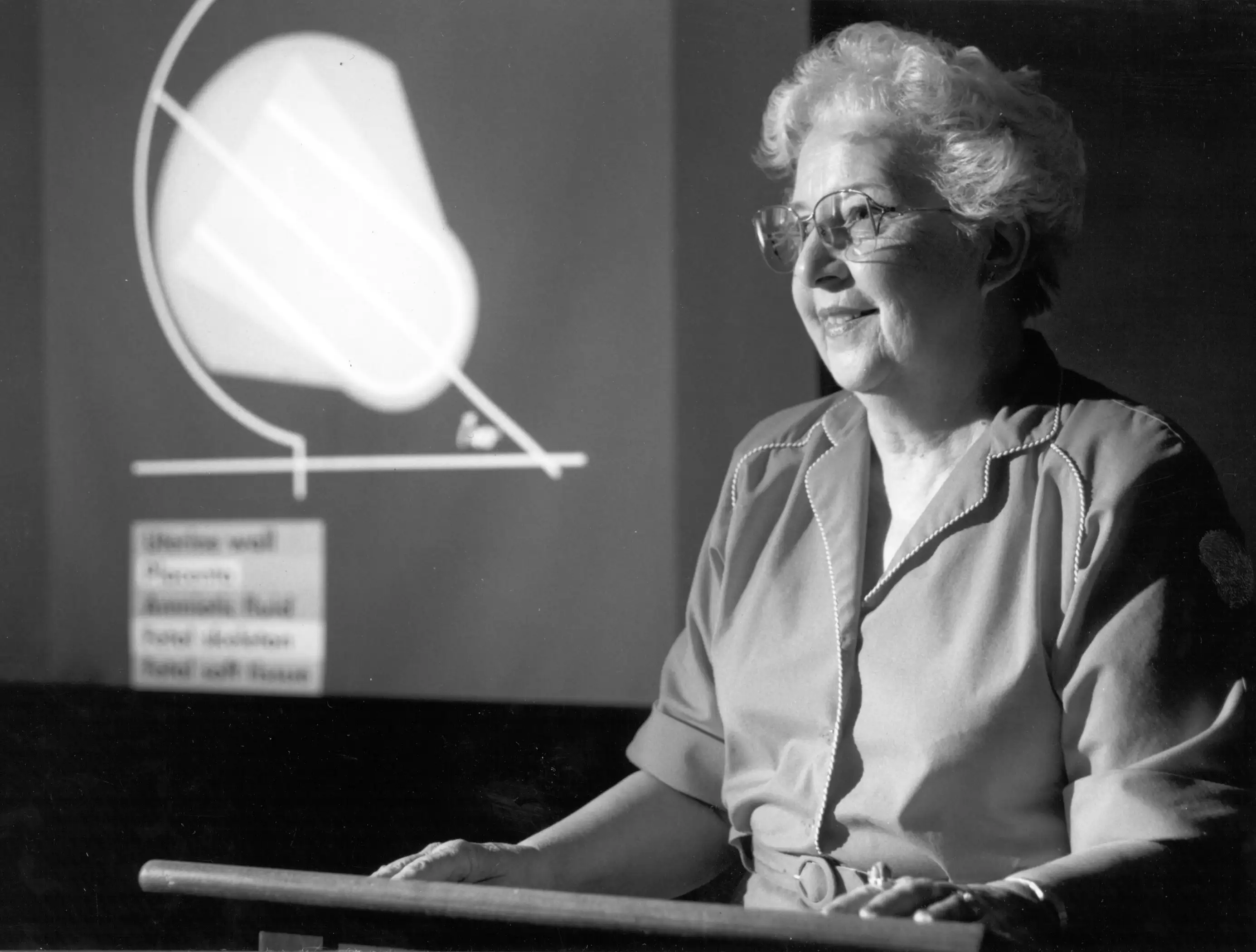

Evelyn Watson, pictured with colleague Jack Beck

So, through the Society of Nuclear Medicine, they started the Medical Internal Radiation Dose (MIRD) committee to help physicians get answers about dosimetry. Cloutier became the chairman of MIRD. Meanwhile, the program Cloutier and Watson built at ORINS became the Radiation Internal Dose Information Center (RIDIC). When Cloutier rolled off the MIRD committee, he asked Watson to replace him. She later became the chairman, too. And, when Cloutier was ready to pursue other opportunities with the government and leave his radiation safety gig, he tapped his protégé, Evelyn Watson, to manage RIDIC which she did for 20 years. She focused particularly on fetal dosimetry for pregnant women.

Because of Watson’s tenacity, her from-the-ground-up research and studying that she committed herself to, she authored or co-authored about 90 papers, edited several industry newsletters and journals and was invited to speak all over the world. Laughter bubbled up in Watson’s oral interview as she recalled her reception in the health physics community: “People called me Dr. Watson. I am an English major. I used to try to correct that, but they didn’t pay any attention to me. Anyway, I was director of what we called RIDIC, which was the internal information center. The staff grew. It just kind of blows my mind at times to think about because I would never have dreamed that would have happened.”

Watson speaking during a special training session

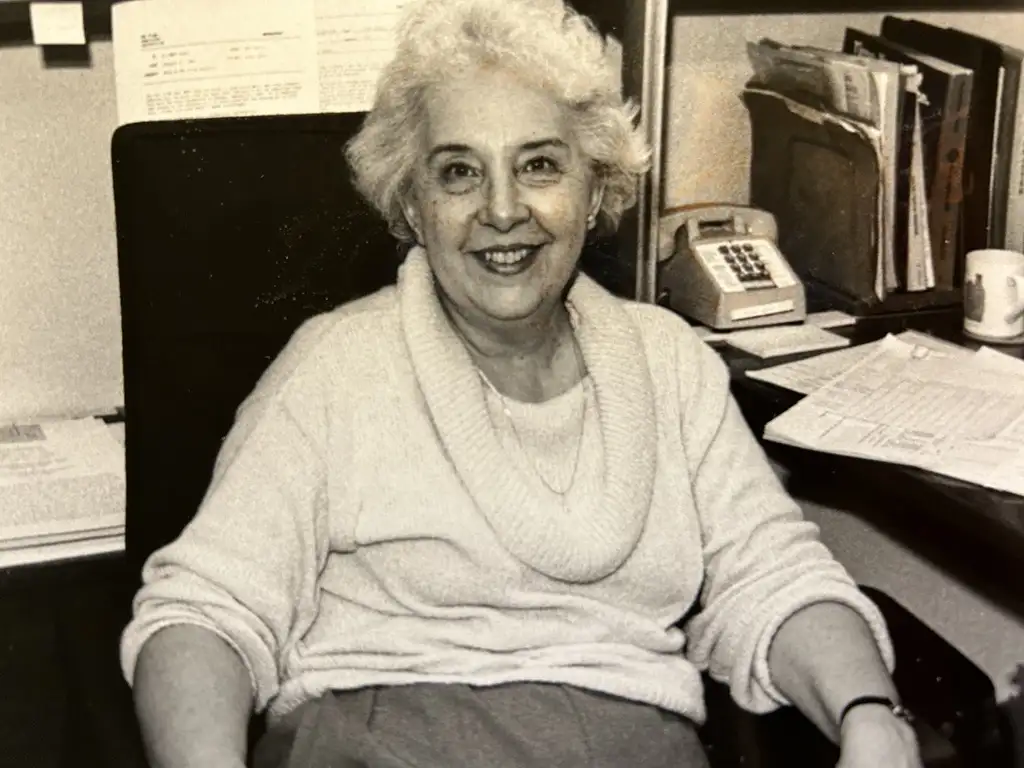

A wall full of awards

In 1994, Watson retired a decorated and celebrated health physicist. Thirty-five years prior, she had quit the company because she didn’t see a future as a records clerk. Life circumstances drew her back in, and many in the health physics community believe the world is better for it.

When the oral interviewer asked Watson about her accomplishments, she joked that she had a wall full of awards—accolades she never anticipated when she collected her English degree at the end of her formal education.

Evelyn Watson during her tenure at ORAU

As she wrapped up her career, Evelyn Watson received the Lifetime Achievement Award from the East Tennessee Chapter of the Health Physics Society and the Lifetime Scientific Achievement Award from the East Tennessee Chapter of the Association for Women in Science (the first-ever recipient of the award). After retirement, the recognition continued. She received the Marshall Brucer Award for Distinguished Service to the Nuclear Medicine Community and was featured in Who’s Who in America 2001—The Chronicle of Human Achievement. And, Watson was the first woman to ever receive the Loevinger-Berman Award for Excellence in Medical Internal Radiation Dosimetry in 2007.

Though Watson is now deceased (Dec. 15, 1928 – Nov. 4, 2016), her legacy will continue to inspire and impact the future of dosimetry for decades to come.