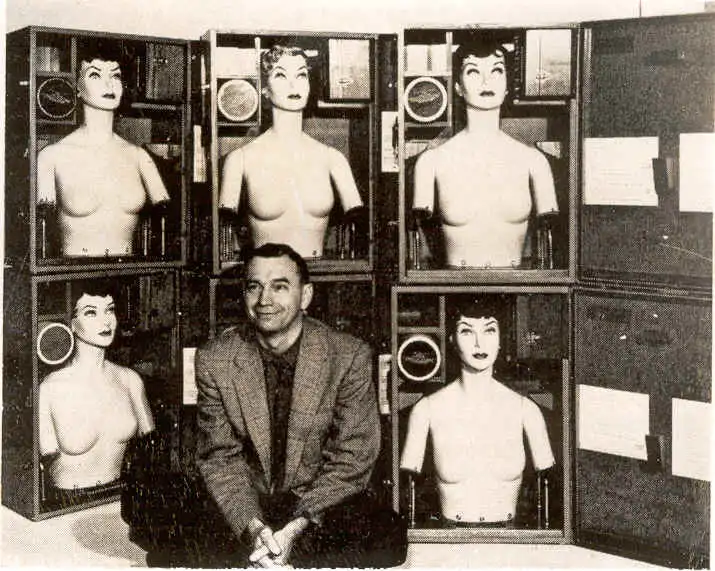

Physician and nuclear medicine pioneer, Dr. Marshall Brucer, created head and neck as well as half body manikins for training. Above, Brucer poses with a few of the manikins he used for training radiation detection.

Did you catch that spelling? Manikin rather than mannequin? The distinction helps set up this topic: while mannequins model clothing in stores, manikins model medical situations. The main difference between manikin and mannequin is that mannequins are stationary models that advertise consumer goods whereas mannikins are more anatomically correct models that are capable of simulating real-life medical scenarios.

In the early 1950s, that’s exactly what Marshall Brucer, M.D., of the Oak Ridge Institute for Nuclear Studies (ORINS- ORAU’s original name) Medical Division hoped to create—a standardized model to simulate iodine uptake in humans. Brucer recognized the need for a more accurate and realistic way to measure radiation exposure in humans. The thyroid gland is particularly susceptible to damage from radiation exposure because it absorbs and concentrates iodine, which is a common radioactive isotope released in nuclear accidents or incidents. That exposure can lead to thyroid cancer or other thyroid diseases. At the time, doctors had been developing ways to measure thyroid function for a few decades. But there was no consistent method for the field of medicine.

Bonnie Boleyn, Brucer’s second scanning manikin, is part of ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity

Doctors had been relying on mathematical models and animal experiments to estimate the risk of radiation exposure. With Dr. Brucer’s concept, he created a manikin (sometimes called a “phantom”) that is about the size of a grown adult female, and it was filled with a material that simulates the density of human tissue. It was made of Lucite, a type of plastic that is transparent to radiation. He gave his first model a name—Anne Boleyn, as a nod to the second wife of King Henry XIII. Brucer described the first scanning manikin this way: "the Anne Boleyn manikin consists of a head and neck. There is nothing in the head. At the base of the head is an artificial neck. Contained within the neck is a movable mock thyroid gland, two fixed metastases, a mock spinal cord filled with mock-iodine and two low-level sets of simulated blood vessels. In the thyroid is a cold spot simulating a nonfunctioning adenoma of the thyroid gland."

In the neck, there was a gel-like substance that contained a chemical that changes color when it is exposed to radiation. Brucer was pleased with his creation, so he made another. He named the second Bonnie Boleyn.

Brucer’s invention was groundbreaking. The manikin simulated the internal distribution of radiation within the human body and could be customized to mimic different body types and sizes. At first, there was only Anne and Bonnie, but they were not the last. The family grew to include Chloe, Drusilla, Eupexia, Felicia, Grenadine, Horense, Ibis, Jezebel, Katrinka, Lulu, Moira, Nabby, Ophelia, Pandora, Queenie, Rhoda, Sara Coma and Terry Toma. (I hope you enjoyed the alphabetical order as I did.) Around the ORINS Medical Division, it was a joke that Dr. Brucer had a harem. What did he do with so many manikins? Brucer loaned them to medical facilities all over the world so doctors could establish the optimal operating parameters of rectilinear scanners and assist personnel in the interpretation of the scan. In this way, Dr. Brucer helped other medical professionals calibrate their tools for consistent measuring.

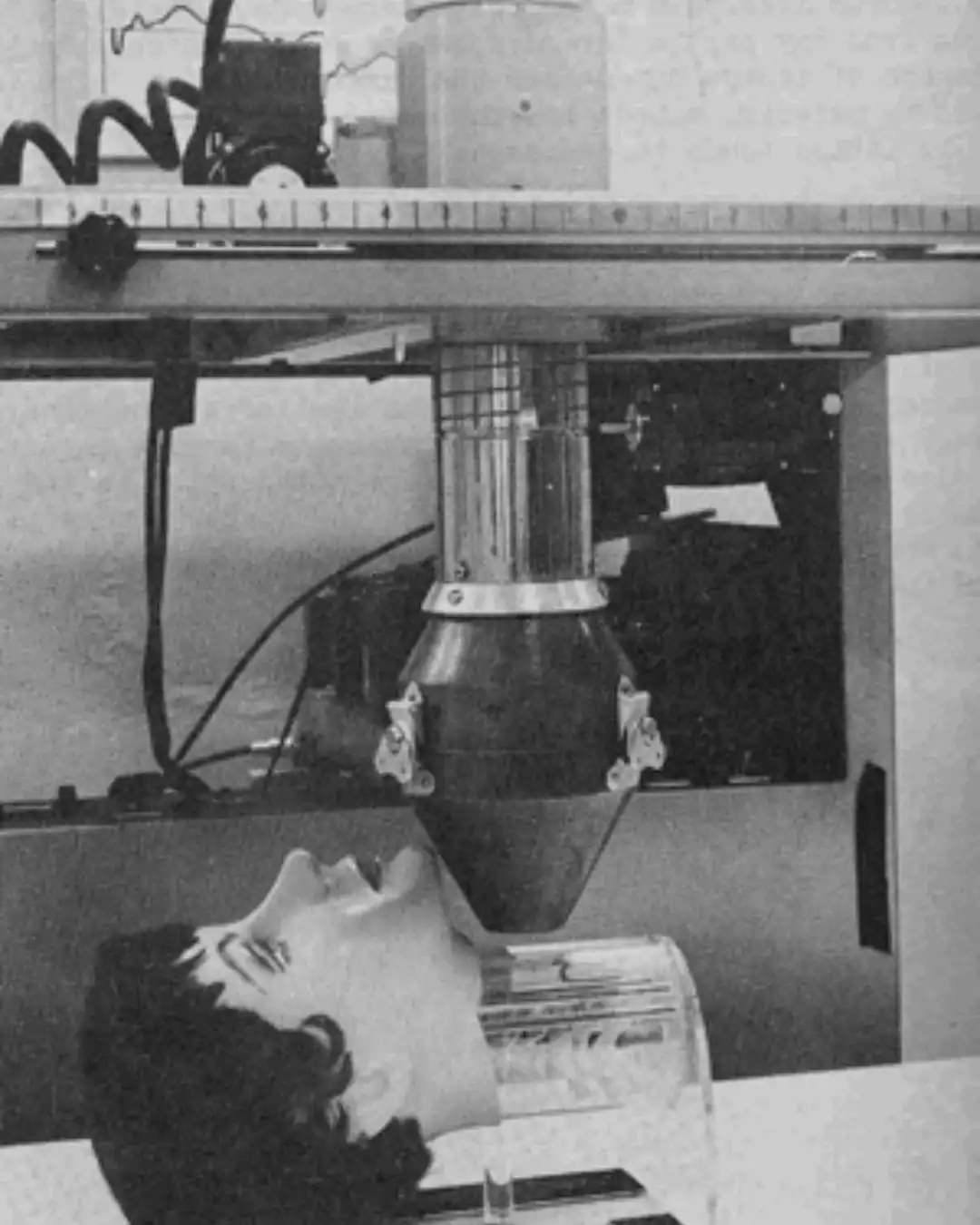

A rectilinear scanner with one of Dr. Brucer’s manikins

Let’s back up and talk about what a rectilinear scanner does. It’s a device used for imaging the distribution of radioactive material within the body. As a systematic sampling instrument, it forms its image by moving over (scanning) the field of interest. In this case, it scanned thyroids. The output was used to generate an image on a piece of paper or photographic film.

The quality of the image, which impacted the physician's ability to interpret the scan, depended on things like the scan rate, the size of the dots used to produce the image, etc.

Physicians could put their skills to the test (and get better) through practice with Dr. Brucer’s manikins.

Some manikins represented hyperthyroidism (when the thyroid produces too much thyroxine hormone). Some manikins represented hypothyroidism (when the thyroid doesn’t produce enough thyroid hormone). And others represented euthyroid (a normal, well thyroid).

While the head and neck phantoms were handy because of their size, it’s important that training with manikins reflects what physicians would see in real patients. That means, moving to half-size manikins would allow doctors to see the iodine “scatter” throughout the body. So, Brucer had both sizes in his “family.”

All of his manikins were used extensively in the 1950 – 60s, and even in the aftermath of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, as using the uptake models helped doctors understand what to expect. In recent years, advances in technology have led to the development of new types of radiation devices that are smaller and easier to use. Like the manikins’ hairstyles, the models themselves have mostly gone out of fashion, but they remain an important tool for researchers and scientists to reference today.