There are lots of incredible items in ORAU’s online Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity. This Nuke Buster is interesting enough to deserve a blog post all to itself. I mentioned it in the blog Measuring Radiation Then and Now, but here is the fuller story.

This device was a donation to our museum’s collection from a hippie commune known as The Farm in southern Middle Tennessee. What’s the connection to ORAU? Allow me to set the stage:

Hippies and a commune

In the late 1960s, a countercultural English and creative writing teacher at San Francisco State College, Stephen Gaskin, held open discussion groups known as Monday Night Class. The gathering attracted as many as 1,500 students and hippies. Growing dissatisfied with their way of life, Gaskin and a few hundred of his followers left California to cross the country in a caravan of rebuilt school busses. They landed in Summertown, Tennessee, in 1971 and purchased just a little more than 1,000 acres. From their commune’s founding, residents took vows of poverty and built their community on the principles of respect for the earth and nonviolence.

Because nonviolence was a fundamental priority to the group, residents of The Farm started attending anti-nuke demonstrations and protesting nuclear power and the U.S. government’s weapons programs in 1978. Activists from The Farm felt defenseless in the event of environmental radiation because radiation is invisible. They reasoned that people should be able to detect radiation, so they can deal with it. After looking at current available tools, The Farm residents thought these options were too big and too expensive. They also thought the products were lacking an alarm—in case they stumbled into a radioactive area—so, they decided to develop their own technology.

Meanwhile, The Farm’s communal economy wasn’t working out very well. So, they reorganized to follow a strategic business model in which each resident had to support himself. Residents of the commune still wanted to be self-sufficient from the outside world, so they would need to use some entrepreneurial spirit. They leaned into their interests and started (or continued) businesses involving printing, publishing, construction, mail order textiles, specialty food products (mostly made of soybeans) and manufacturing electronic instruments.

Nuke Busters

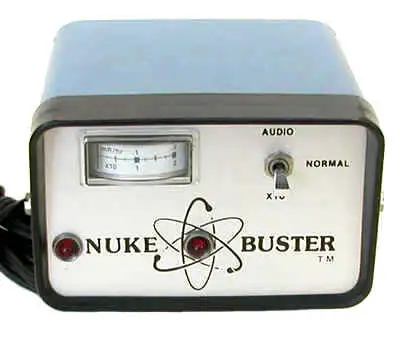

Those interested in electronic instruments started a company called Solar Electronics which produced solar-powered two-way radios that could be used in remote locations. From there, they worked on several projects including a fetal heart monitor and ultimately radiation detection equipment. One of their most popular innovations was the Nuke Buster. It was portable and plugged into a car’s dashboard cigarette lighter. With it, you could monitor counts per minute either with a chirper or an electronic display. The central red light comes when it detects radiation levels about four times that of background radiation and the main alarm goes off as levels increase.

This Nuke Buster can be viewed in ORAU’s online Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

In the aftermath of the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant accident in Pennsylvania, business for Solar Electronics’ radiation alert products boomed. These items sell well to this day helping the company (now renamed SE International) to an annual gross of about $1 million.

In conjunction with the business and commune clinic, resident Steve Skinner attended one of ORAU’s Professional Training Programs in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, for radiation safety. Skinner needed a license to operate an X-ray machine at the clinic. Through that experience, he got to know health physicist and trainer Dr. Paul Frame—who also happens to be the curator of ORAU’s online Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity. Skinner generously agreed to donate the Nuke Buster to our collection. And, that is the story of how hippies, communes and Nuke Busters intersected with ORAU.