Jump to: Nuclear fallout fear | The fallout shelter plan | Fallout shelter signs

In ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity, Paul Frame, Ph.D., has collected historical items that tell the story of how humanity has tried to harness the power of the atom: using radiation in weapons, medicine, commercial use and more. It seems people have always been in awe, whether out of respect or more often fear, when it comes to man interacting with radiation.

Family huddles in stocked fallout shelter for photo in 1955. Photo by: Underwood Archives/Getty Images.

In our museum’s collection, you will see a lot of different items that relate to fallout shelters because there was a period of time when the U.S. government grappled with the consequences of nuclear weapons and how citizens could respond if our enemies used the technology against us. (Today, more than 50 years later, our security in our ongoing nuclear deterrence policy leaves us a little more comfortable than where we were in the 1960s.) But as the reality of atomic weapons dawned, our leaders had to figure out what was next.

From supply checklists to how-to instructions that the government distributed to the masses, this blog will share highlights from ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity as well as the Office of Civil Defense’s informational campaign to educate the public about their plan to identify and stock shelters that could be used in the event of an atomic weapons attack.

Nuclear fallout fear

For those who grew up after the Cold War ended, it’s hard to comprehend what life looked like when one of the U.S. government’s top priorities was to create a network of fallout shelters across the country. In 1961, Congress voted to spend more than $169 million on structures in which American citizens could take refuge to protect themselves from nuclear fallout. The math on an equivalent amount today is more than $1.7 billion!

See this board game and more in ORAU’s Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

When the U.S. ended World War II in 1945, there was a collective sigh of relief across the globe. The ease didn’t last long though because the Cold War began in 1947 with strong ideological differences between what had been the Axis and Allied powers during the Second World War. The Russians detonated an atomic weapon in 1949 in Kazakhstan, and the Soviet threat put Americans back on edge.

From the late 1940s through the 1950s, the U.S. government needed uranium for nuclear reactors and stockpiling weapons. So, the Atomic Energy Commission offered fixed rates for uranium ore and bonuses for people who found new deposits. It was the uranium rush! Like the gold rush 100 years earlier, prospectors went in search of uranium out West. The get-rich-quick spirit inspired movies and even board games.

The 1960s took a more somber tone as the possibility of nuclear holocaust loomed with the Berlin Crisis and Cuban Missile Crisis. This is the decade that “fallout shelters” entered the American vernacular, and the pervasive fear of nuclear fallout continued into the 1980s. The Federal Emergency Management Agency distributed a “Radiation Safety in Shelters” handbook in 1983 with this notice on the front cover:

So, how were fallout shelters going to save U.S. citizens? Let’s look at the government’s plan to prepare for the worst.

The fallout shelter plan

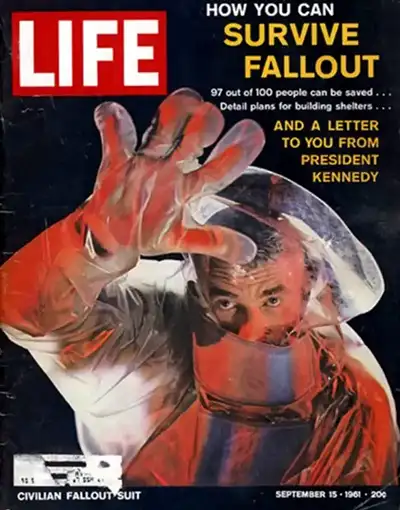

Learn more about the fallout history sign including this Life magazine cover in Bill Geerhart’s blog in ORAU’s online Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

As the Kennedy administration kept their eyes on the Soviet Union, they called on citizens to take the possibility of nuclear attack seriously and make individual and community response plans. The Department of Defense’s Office of Civil Defense shared information through pamphlets, public addresses, videos and even a publication in Life Magazine.

As the official video from the Department of Defense explained, they believed tens of millions of lives would be saved in the event of a nuclear attack if shelter space was made available.

Early on, officials admitted there was little that could be done to protect those in the immediate area of a nuclear blast, but urged people to remember that those unaffected by the blast may be in harm’s way from fallout radiation that could spread throughout most of the country. Through the literature they distributed and the videos they produced, they explained that there’s only one protection against radiation: shielding. That is, putting something substantial between you and the penetrating gamma rays. Ideally, the government wanted people to shelter behind two to three feet of concrete or earth.

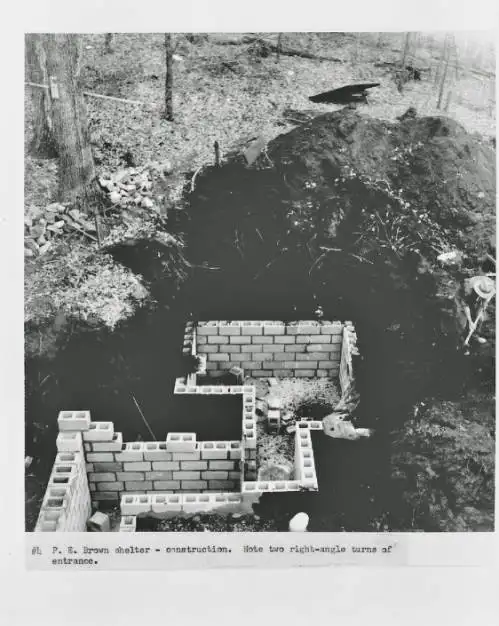

This excerpt from a Civil Defense Bulletin was printed in May of 1958. You can see the full pamphlet in ORAU’s online Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity. P.E. Brown’s fallout shelter under construction in 1959. Photo is part of the Municipal Oak Ridge Photograph Collection.

In this photo from the Oak Ridge Public Library Digital Collection, you can see a man at the far right digging out this fallout shelter for an earth and cinder block shielding spot.

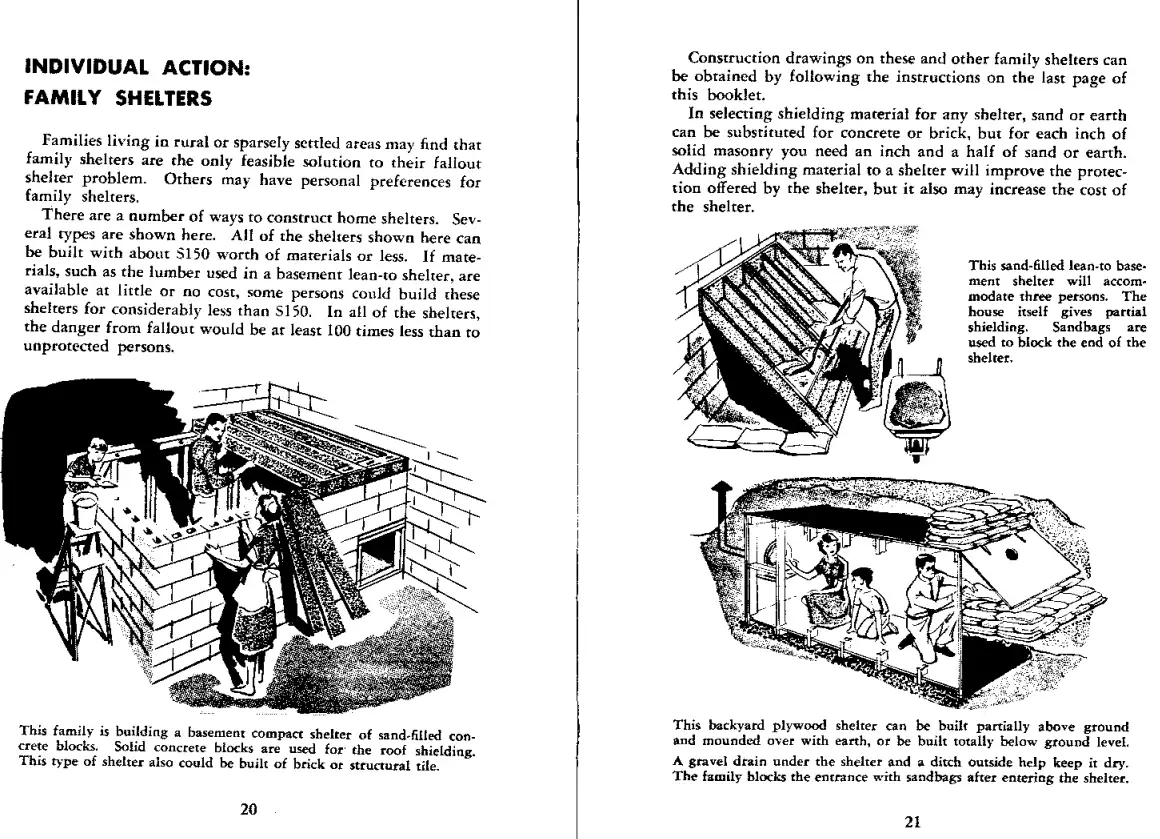

For homes that had basements, the government shared information advising homeowners how to “improvise and create shelters on [their] own.” (.PDF)

This photo shows a woman making a bed in her home fallout shelter.

Fallout shelters were intended to protect a family from drifting radioactive fallout from nuclear attack and were stocked with enough supplies for two weeks. Photo by: Maxie Roberts, The State Media Company (Columbia, S.C.)

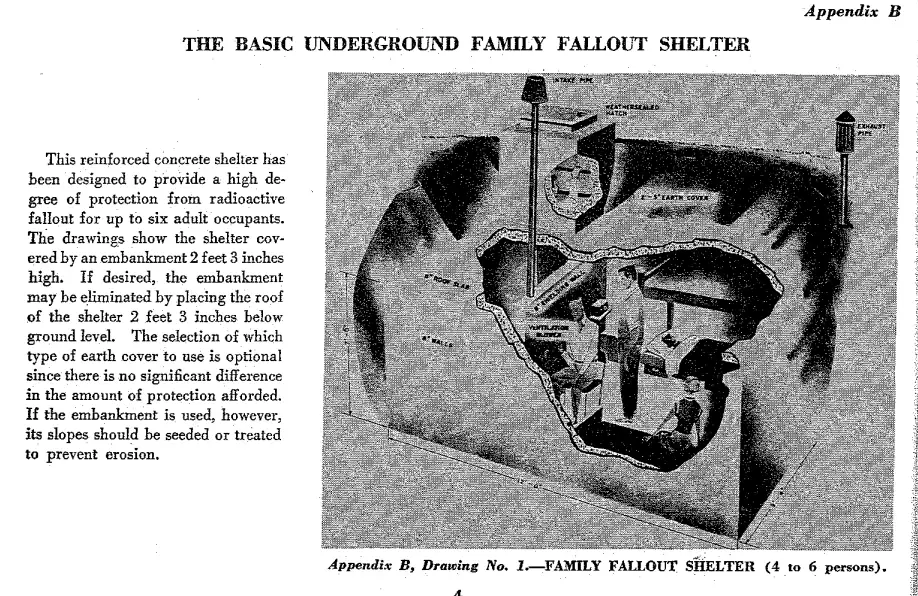

One of the most widely distributed pamphlets was titled “Fallout Protection: What to Know and Do About Nuclear Attack.” It provided visual diagrams for what some of these shelters could look like—complete with step-by-step instructions for how to build them.

View a full copy of Fallout Protection: What to Know and Do About Nuclear Attack in ORAU’s online Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

Not everyone would be able to build their own fallout shelter, so, the Office of Civil Defense organized a nationwide “Shelter Survey” in August of 1961. The government sent out questionnaires and wanted responses about public buildings such as schools, hospitals and office spaces. The Office of Civil Defense planned to compile an inventory of all structures that could fit 50 people or more that had a protection factor of 100 (that means the people who used this shelter were 100 times more likely to survive if they were inside the building versus being outside the building), though, the Office of Civil Defense was willing to consider structures with a lower protection factor because they could make upgrades to improve the protection.

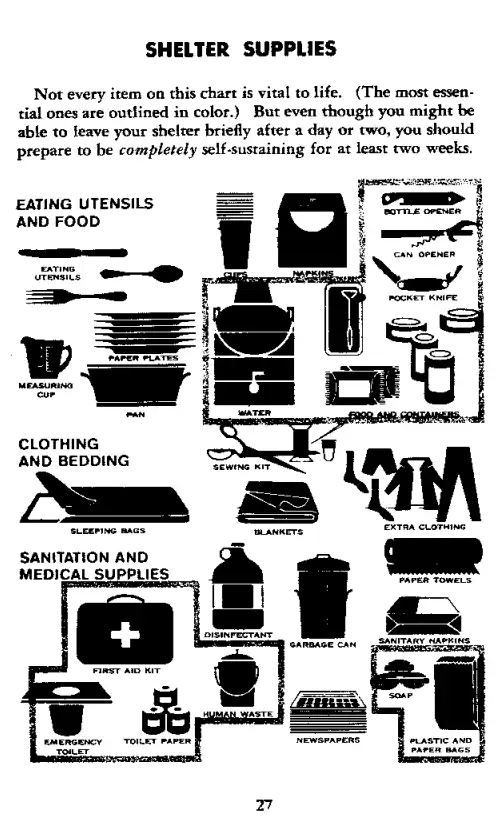

This list appeared in the Fallout Protection: What to Know and Do About Nuclear Attack booklet, which can be viewed in ORAU’s online Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

Once shelter facilities were identified, the next step was to stock them with supplies necessary for survival. This phase of the program fell under the direction of the local civil defense officials who received supplies from the federal government. The supply list included two weeks’ worth of food, water, sanitation and medical supplies as well as radiation detection equipment.

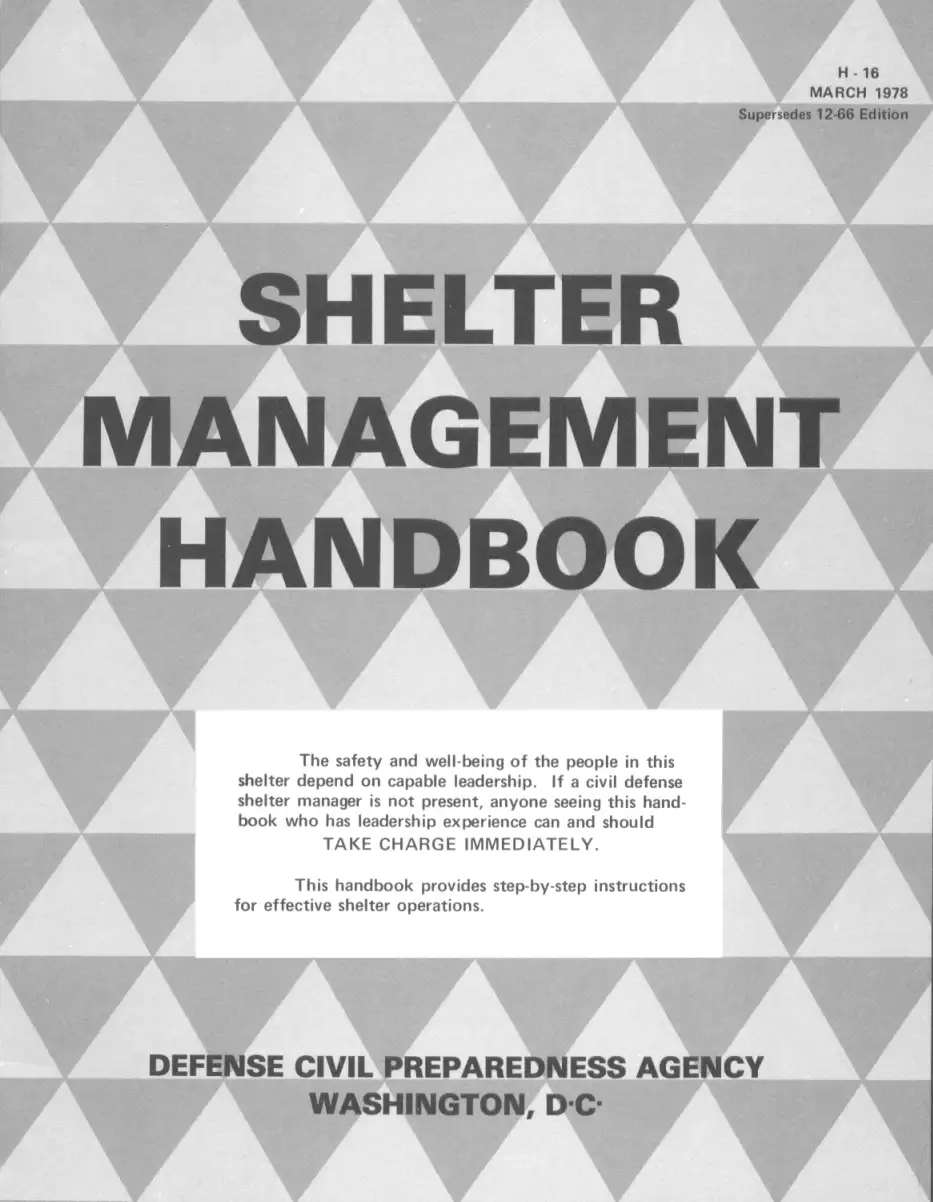

Read the full Shelter Management Handbook in ORAU’s online Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity.

The Office of Civil Defense also thought through who should take charge of the shelters. They even left copies of their Shelter Management Handbook in the prepared spaces ready to be used. The front cover reads: The safety and well-being of the people in this shelter depend on capable leadership. If a civil defense shelter manager is not present, anyone seeing this handbook who has leadership experience can and should TAKE CHARGE IMMEDIATELY. This handbook provides step-by-step instructions for effective shelter operations.

Fallout shelter signs

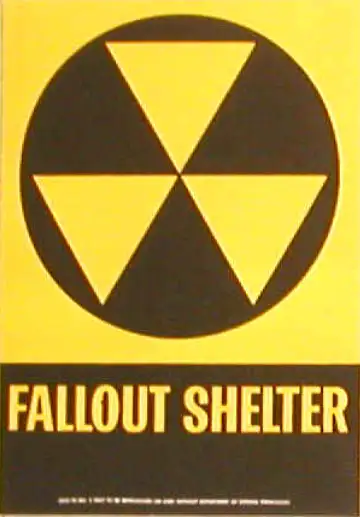

The campaign to educate the public about fallout shelters included recognizable branding. Civil defense leaders negotiated a contract for the production of 400,000 outdoor fallout shelter signs and one million indoor signs.

You could say it was the sign of the times: three yellow inverted triangles on a black and yellow background. Psychologists explain that it was the best design to capture attention and be recognizable from 200 feet away.

Fallout shelter design

The sign, like the fallout shelter campaign, sent a strong message: the U.S. was going to do what it could to prepare and protect its citizens. Would this plan have worked? We never got to see the plan in action because, thankfully, nuclear warfare has not come to American soil.

By the late 1970s, the fallout shelter program was discontinued. At that point, many of the shelters fell into disrepair or became storage rooms as they were decommissioned. Most of the fallout shelter signs have been removed, but if the structure is standing, it’s shielding would still offer protection (it is not likely stocked with supplies, though!).

Our foreign policy of nuclear deterrence has been effective so far. Let’s pray future generations won’t experience the fallout fear that plagued the United States in the 1960s.